Post-War Reality

The brutality and totality of the First World War came as a shock to many in Europe. The conflict claimed 9 million lives, of which over 4 million were civilians, and left 20 million wounded and impaired. The war ravaged the cities and brought an end to the world people had known. La Belle Epoque was over, the new political map of Europe was drawn, and the countries and their traumatized societies had to be rebuilt or formed from scratch.

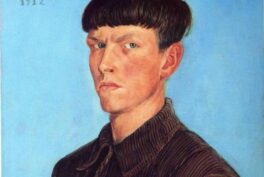

The new situation required new ways of depicting reality. In Germany, the formal experiments of the avant-garde art of the early 20th century, especially Expressionism, were not able to exude the social-political turmoil that was happening. This gave way to artists like Otto Dix, Max Beckmann, George Grosz, and Lotte Laserstein to experiment with a new version of realist art—sober, objective, and heavily influenced by the contemporary situation.

The New Objectivity

The movement’s name came from the title of the exhibition New Objectivity: German Painting since Expressionism curated by Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub at the Kunsthalle Mannheim in 1925. The New Objectivity (or The Matter-of-Factness as it is sometimes translated) focused on the matter, the object, something real and specific—unlike Expressionism, which was obsessed with creating a new reality out of the artist’s emotions and inner experiences. Expressionism was separated from the political context, while the New Objectivity voiced social issues, revolutionary politics, and criticism of bourgeois society.

Stylistically the New Objectivity mixed different modern influences, among them Dadaism, Cubism, and Expressionism. It also encompassed a variety of styles, from the precise realism of Christian Schad to cartoonish depictions of George Grosz.

Despair and Hedonism

Following the war, the anger, pain, and resignation was experienced by many citizens in Germany, yet they were accompanied by hope and excitement for the possibilities the Weimar Republic had in sight. All these can be seen in the works made in the late 1920s. Many of the artists experienced the horrors of the First World War firsthand. A big part of their art was therefore dealing with the atrocities, innocent victims, and scarred soldiers—like in the case of the etchings of Otto Dix. Furthermore, the marginalization of war veterans and the poor, working class in the Weimar Republic is also clearly visible in works by George Grosz and others, often presented using satire or grotesque language.

However, the war trauma was only one side of the story. “The Golden Twenties” was also a time of excitement and celebration of life. Sexual freedom, the rapidly growing amusement industry, and technological developments all contributed to the joy expressed within German cities. The decadent atmosphere was especially felt in Berlin, which offered an alternative, underground culture of cabarets, clubs, and theaters that often allowed homosexual and transgender clientele. One of the icons of Berlin’s hedonist life was an erotic dancer Anita Berber portrayed by Otto Dix.

This multifaceted society, with all its highs and lows, was at the center of the attention of German artists. Some of the portraits of the time surprise us to this day with their modern feel and uncompromising nature. All these themes that inspired the New Objectivity can be explored throughout the exhibition.

The New Woman

Another important aspect of the late 1920s that had a great impact on the New Objectivity was the social upheaval regarding women and their role in the post-WWI society. The exhibition dedicated a separate part to this phenomenon. The emancipation of women, the introduction of their voting rights, and their greater involvement in public life in general manifested in a new, modern image. In fashion, the female figure was liberated from the restrictive corset and an androgynous, more masculine look, with flat breasts and hips, bob cuts, and pantsuits, was taking over. Short dresses and looser, more comfortable outfits allowed freer movement perfect for active lifestyles which included practicing sports and attending jazz parties.

This visual deconstruction of gender roles was visible in the art of the New Objectivity artists, who included women as well—among them Lotte Laserstein, Lea Grundig, Jeanne Mammen, Dodo, and Kate Diehn-Bitt. One of the main highlights of Leopold Museum’s exhibition is The Tennis Player by Lotte Lasertein. The painting presents Traute (Gertrud Rose), Laserstein’s favorite model, resting in between a tennis match.

The androgynous, sporty look of the player (with a tanned body! Something unthinkable in the 1800s), looking away, unbothered by the viewer, is a prime example of the independent woman of the 1920s. The realistic manner of the work, soft, golden light, and abstract patterns of the dress and net create a modern, yet almost melancholic composition, which, according to Hans-Peter Wipplinger, was partly influenced by fashion photography.

The Degenerate Art

The New Objectivity came to an abrupt end in 1933 with the fall of the Weimar Republic and the Nazis taking over the power in the country. Most of the modern artistic expression, and New Objectivity, in particular, was deemed “degenerate art.” The naturalistic, often satirical manner, drenched with anti-bourgeois and Marxist ideas, did not fit Hitler’s vision of art.

Soon the “degenerate artists” faced persecution—they were dismissed from the art academies and associations, while their houses and studios were searched by the police. The works of the New Objectivity were banned from exhibitions, seized by the authorities, or even destroyed. Facing these hardships, many artists decided to leave the country, some withdrew from artistic life, while others turned to support the regime. Those who opposed the new political reality faced further persecution, including concentration camps during the Second World War.

The exhibition Splendor and Misery: The New Objectivity in Germany is on view at the Leopold Museum in Vienna, Austria, from May 24 until September 29, 2024.