Masterpiece Story: Self-Portrait by Faith Ringgold

Self-Portrait by Faith Ringgold is a masterpiece of 1960s portraiture, feminist art, and Black...

James W Singer, 3 November 2024

4 November 2024 min Read

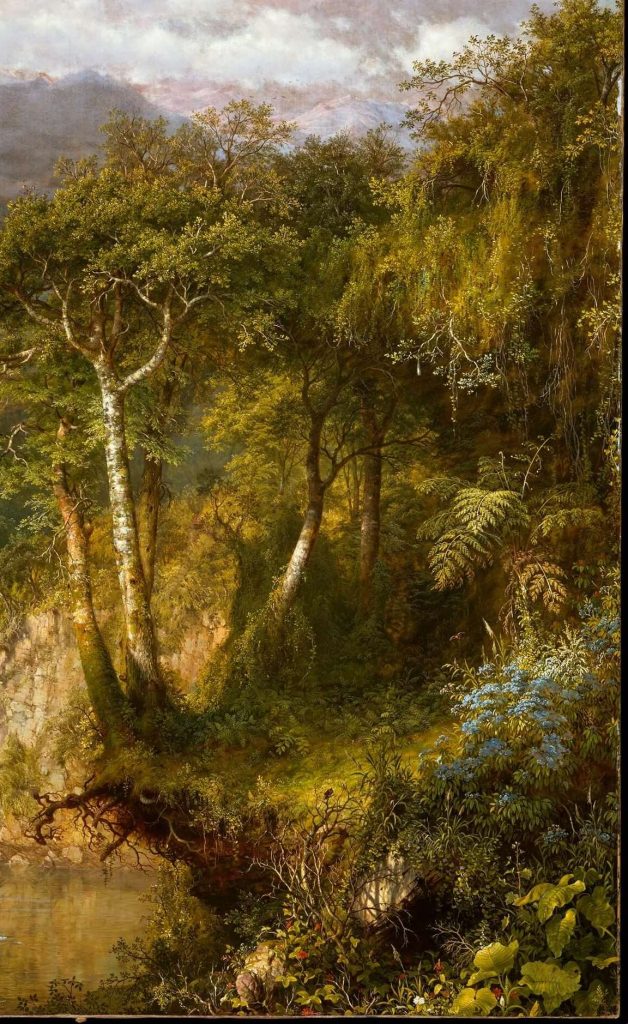

Heart of the Andes is one truly impressive landscape painting. Frederic Edwin Church’s crowning achievement depicts the scenery he saw during his two visits to South America. However, one of the painting’s most important features doesn’t appear on the canvas at all – the pioneering scientist who was the inspiration behind it.

Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900) was among the most celebrated members of the American landscape painting movement the Hudson River School. As the name suggests, the school is most closely associated with American scenery, but Church is better known for his paintings of foreign settings. He traveled all over the world, his journeys were partly inspired by the works of Alexander von Humboldt.

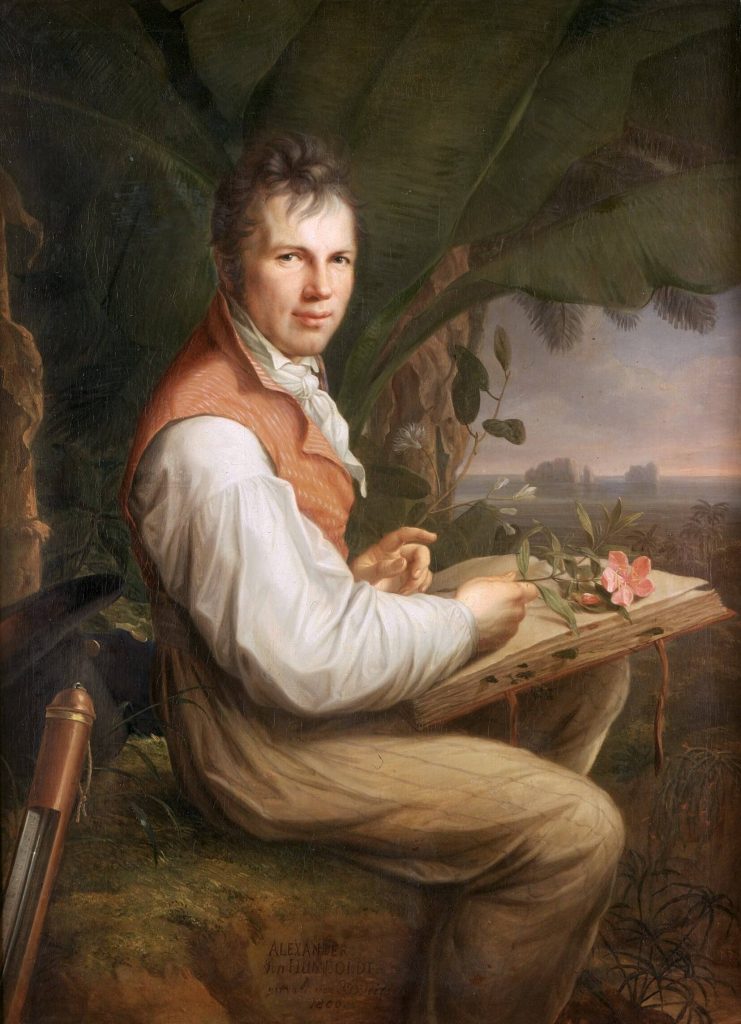

Hero to Enlightenment-era intellectuals everywhere, Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) was a Prussian explorer, natural scientist, and writer. Think of him as a sort of grandfather to most disciplines of modern natural science. Humboldt’s books, notably the five-volume Cosmos, were best sellers in many languages. Among his numerous contributions to natural science, he was the first person to realize that all the world’s ecosystems are interconnected.

If his name sounds familiar, that’s because he’s had so many geographic features named for him. Humboldt wasn’t just any old scientist, however. He was brilliant, collaborative, a fervent abolitionist, and a supporter of Indigenous rights. Humboldt took an expedition through South America in 1799-1804, a voyage that later inspired his admirer Church’s own pair of trips there.

Humboldt was keenly interested in the kinship between art and science. In volume two of Cosmos (1849), he wrote specifically about landscape painting and gave advice to the current generation of artists, such as:

To apprehend these characteristics [of a region’s landscape], and to reproduce them visibly, is the province of landscape painting; while it is permitted to the artist, by analyzing the various groups, to resolve beneath his touch the great enchantment of nature — if I may venture on so metaphorical an expression — as the written words of men are resolved into a few simple characters.

Alexander von Humboldt, Cosmos: A Sketch of a Physical Description of the Universe, trans. E. C. Otté, Henry G. Bohn, 1849, London.

He suggested that a good landscape painter should make an effort to deeply understand the natural world. He also thought that more landscape painters should visit and depict South America. Frederic Church took Humboldt’s advice on every level. Although the two never met or even corresponded, art historian Eleanor Jones Harvey has characterized Humboldt as Church’s “distant mentor.”

In particular, Heart of the Andes expresses Humboldt’s ideas about the “unity of nature” in visual form. In doing so, it makes a very persuasive claim for Church as exactly the kind of ideal landscape painter Humboldt called for in his writings. For this reason, Church became known as “the American Humboldt”, a title that surely pleased him.

Frederic Edwin Church painted Heart of the Andes after visiting Colombia and Ecuador in 1853 and 1857. He and his traveling companions used Humboldt’s writings as sorts of travel guides, often visiting the very same sites as Humboldt had. In a way, Heart of the Andes represents a visual record of Church’s experiences. He made copious sketches along the way, often annotating them with extensive observations. Many of these sketches now reside at the Cooper-Hewitt in New York. He then used this reference material to paint Heart of the Andes back in his New York studio. His full oil study for the work is still at his home, Olana.

Humboldt’s influence shines through in the meticulous detail found throughout the painting. Specialists can identify more than 100 species of South American plants in the painting because Church depicted them so faithfully. These impressive details, which stretch from the immediate foreground all the way into the distance without diminishing clarity, stunned and even overwhelmed many viewers. Anybody who has ever seen the painting in person will understand this feeling. The effect in photographs can’t possibly compare.

Humboldt believed it necessary to understand all the minutia of the natural world in order to comprehend how it all fits together in the big picture. Heart of the Andes did this in visual form by weaving scores of tiny, carefully observed details into a vast-but-cohesive composition. It measures 66 1/8 x 120 3/16 in, (168 x 302.9 cm) and took Church over a year to paint. Obviously, he had learned his lessons well from reading Humboldt.

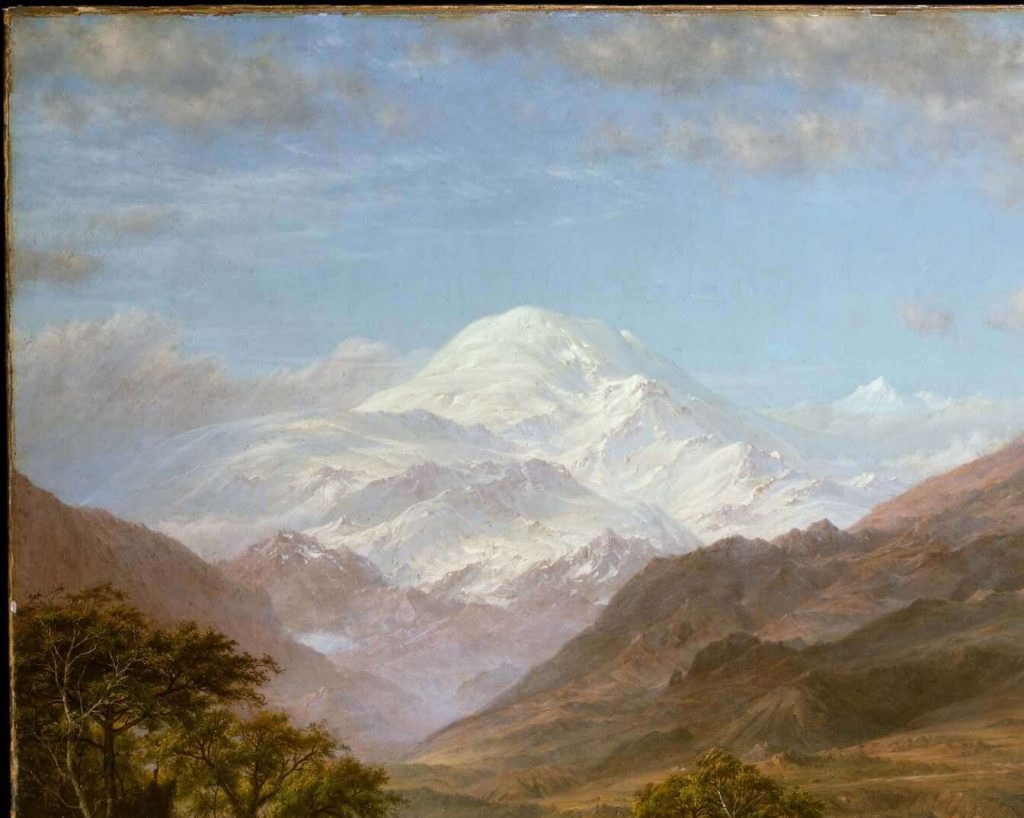

Although Heart of the Andes gives the very convincing impression of depicting a single location, it actually represents at least five different bio-regions in the Ecuadorean Andes, from the lush rainforest to the snow-capped peak of Mount Chimborazo. Colloquially referred to as Humboldt’s Mountain, Chimborazo was particularly significant to the great naturalist. The observations he made while climbing contributed significantly to his theories. Chimborazo was also a focus of Church’s second trip to South America, where he sketched it from multiple viewpoints. Other areas of the painting represent different sites that Church visited nearby. The landscape in the middle distance, for example, is based on the countryside near Quito.

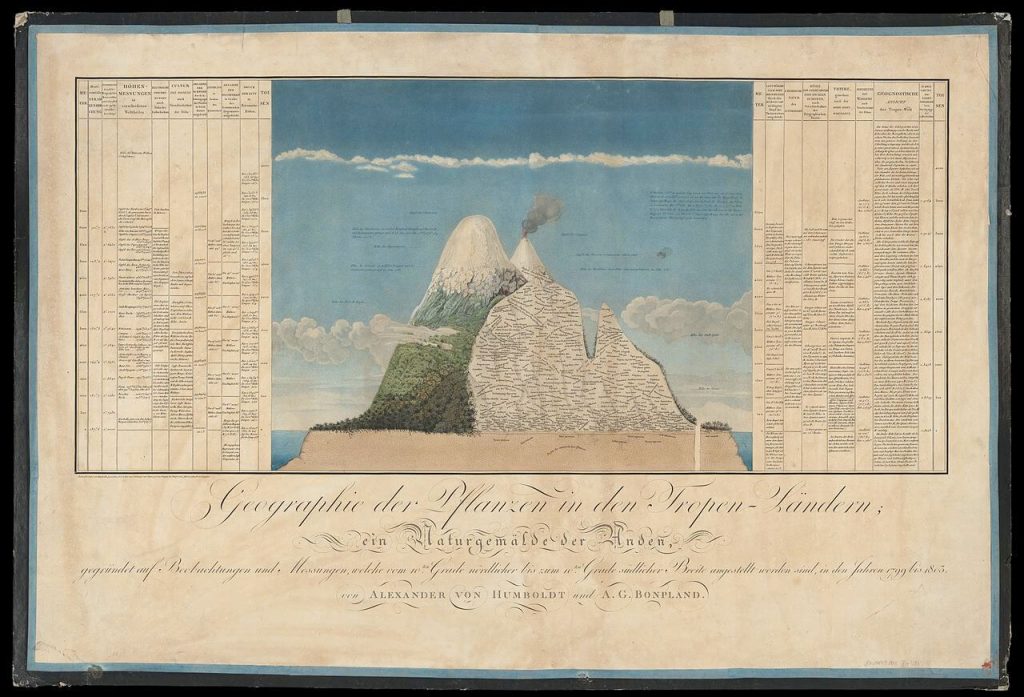

Church based the composition of Heart of the Andes on Humboldt’s 1805 Plant Geography Map. In that illustration, Humboldt recorded the flora he found on Chimborazo and Cotopaxi (another mountain in the Ecuadorean Andes) at various altitudes and cross-referenced this data with other mountain ranges across the world. The correlations he found thus formed the basis for his ideas about the unity of nature. In some ways, Heart of the Andes aspired to do the same thing by combining scenery from different climates into one painting. It shows the vast ecological diversity found at different altitudes in the same location. More than just a painting, Heart of the Andes is almost a visual expression of Humboldtian thought. Humboldt would have been proud.

Church painted Heart of the Andes partly as a tribute to Humboldt. He had planned to send the finished work to him in Berlin, but unfortunately, Humboldt died before it could reach him. Church was devastated.

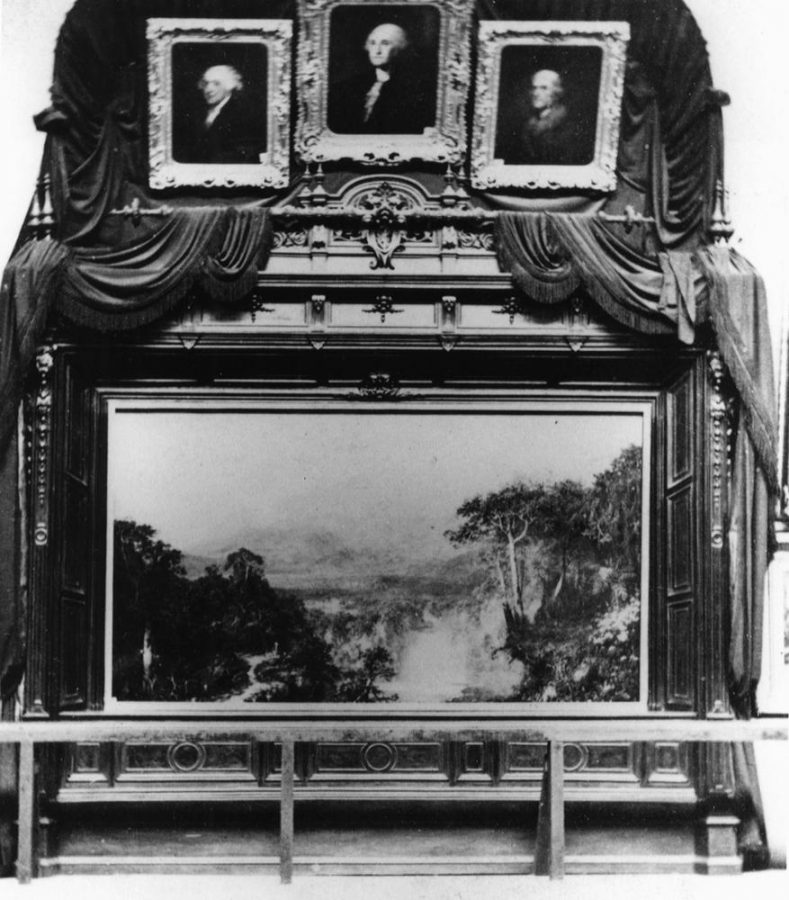

Although Alexander von Humboldt may never have gotten to appreciate Heart of the Andes, plenty of other people did. From 1859-60, the painting appeared in a Great Picture exhibition, a type of early blockbuster involving a single artwork. Such an exhibition of Niagara Falls in 1857 had already put Church in the spotlight, but Heart of the Andes would make him even more famous.

Heart of the Andes had its public debut in New York City on April 27, 1859. The show opened at Lyrique Hall on Broadway but soon transferred to the Tenth Street Studio building, the same place where Church had painted it. Within three weeks, 12,000 people had seen it, often waiting in line for hours to do so. Furthermore, it was the single biggest art event of Civil War-era America.

A deep frame, designed to invoke a window, capitalized on the painting’s illusionism. (Even today, when the painting appears in a more traditional frame, the sense of it being a window onto the Andes persists.) Two of Church’s supporters wrote and sold guides to the painting, while many viewers brought opera glasses for optimal viewing of its details.

Although Heart of the Andes was undoubtedly popular, it garnered mixed reviews. Many people loved it, including American writers Washington Irving and Mark Twain. On the other hand, some critics and spectators found the details to be too overwhelming and the composition not harmonious enough. The painting’s excessive illusionism and relationship to popular (aka low-brow) panorama shows also received negative comments. Regardless, commentators recognized its connection to Humboldt.

Overall, Church had every reason to be pleased. He reached a new level of fame and respect, while the 25-cent admission price made him and his promotors a small fortune. Following its New York unveiling, Heart of the Andes went on a two-year-long tour that included seven other cities in America, plus London. It was a hit everywhere. London critics raved about it, comparing Church to Claude Lorrain, J.M.W. Turner, and the Pre-Raphaelites.

More than 30,000 people saw it in Boston, a record at that time. Scottish printmaker William Forrest made an engraving of it for sale by subscription. And on top of all this, a wealthy New York collector William T. Blodgett promised to buy Heart of the Andes for the huge sum of $10,000 before the tour even started. As a result of this success, a steady stream of private collectors commissioned South American scenery paintings from Church.

Heart of the Andes eventually found its way to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, an institution that Church and Blodgett both helped to find. You can still see it there today.

In 2020, the Smithsonian American Art Museum hosted Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature and Culture exhibition. Works by Frederic Church were featured heavily in this major exhibition about Humboldt’s impact on American culture. Heart of the Andes, although key to the exhibition’s ideas, did not actually appear (it rarely leaves the Met). However, the curator Eleanor Jones Harvey narrated a great, immersive video about the painting’s main features. Unfortunately, the exhibition closed early due to COVID-19.

Kevin J. Avery. Church’s Great Picture, The Heart of the Andes, Exhibition catalogue, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1993.

Kevin J. Avery. Treasures from Olana: Landscapes by Frederic Edwin Church, Hudson, NY: The Olana Partnership, 2005.

Kevin J. Avery. Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900), in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. (August 2009). Accessed 6 Dec 2021.

Eleanor Jones Harvey. “Alexander von Humboldt and ‘Heart of the Andes’: An Immersive Journey“, Video, Smithsonian American Art Museum, April 13, 2020. Accessed 6 Dec 2021.

Eleanor Jones Harvey. Capturing the Cosmos in: Frederic Church’s Olana on the Hudson: Art, Landscape, Architecture, Julia B. Rosenbaum & Karen Zukowski eds. New York: Rizzoli Electa and The Olana Partnership, 2018, pp. 91-101.

Eleanor Jones Harvey. Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature and Culture, Princeton & Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2020, pp. 86-90, 313-372.

Julia B. Rosenbaum. A World in View in: Frederic Church’s Olana on the Hudson: Art, Landscape, Architecture, Julia B. Rosenbaum & Karen Zukowski eds, New York: Rizzoli Electa and The Olana Partnership, 2018, pp. 45-66.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!