Masterpiece Story: Allegorical Painting of Two Ladies

Allegorical Painting of Two Ladies is an enigmatic and highly unusual imaginative portrait made in 1650s England. It reveals a fascinating story...

Nicole Ganbold 14 October 2024

Africa is a beautiful continent filled with sweeping landscapes and mighty rivers. Its history is filled with great kingdoms and large empires. Its artistic legacy first began within its deep prehistory and stretches across the millennia towards the present. With such a rich heritage stretching over eons and one-fifth of the world’s landmass, why is African art not studied, promoted, and showcased as much as Western art? There are so many pieces of extraordinary power, beauty, and complexity just waiting to be experienced. One magnificent piece is Queen Mother Idia of Benin, created in the Kingdom of Benin during the 16th century. The art history of Africa needs revision, and this masterpiece proves why.

The Kingdom of Benin was founded by the Edo People during the 13th century on the western border of the Niger River. The kingdom controlled the mouth of one of the three biggest rivers in Africa (Niger, Congo, and Nile) and therefore controlled a great trade route. This civilization hence grew and expanded in the area of modern Nigeria in West Africa– centering their kingdom around the capital of Benin City. They reached their greatest power and territory during the 15th and 16th centuries when their influence and borders stretched from the Niger Delta in the east to the Lagos Lagoon in the west. It was during this energetic time and place that the masterpiece Queen Mother Idia of Benin was created.

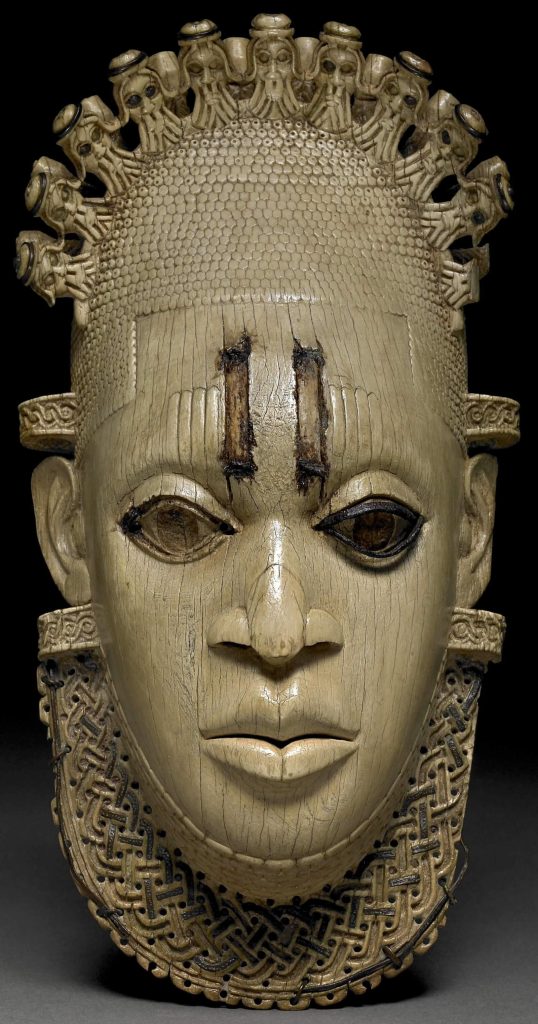

It is a pendant mask made of elephant ivory, iron, and copper alloy. It was designed to be worn suspended on the chest or hips during important ceremonies by the two large side hoops framing the face. It is quite small at 9.6 inches high, 4.9 inches wide, and 2.4 inches deep (24.5 cm H, 12.5 cm W, and 6 cm D). However, its compact size does not undermine its majesty. Queen Mother Idia of Benin is one of the finest ivory carvings from Benin and possibly from all of Africa. It is intricately carved and inlaid to form a sensitive and idealized portrait of a strong noblewoman known to Benin history as Queen Mother Idia.

Queen Mother/Iy’oba Idia was a warrior queen who led many armies into battle. She aided her son, King/Oba Esigie (r. 1504-50), on his military campaigns and was known locally as “the only woman who went to war.” Iy’oba Idia was therefore highly revered by her son and his people. Oba Esigie commissioned this work and four other ivory pendants to commemorate his strong and powerful mother. These five pendants are similar in style and appearance, but the British Museum example is the most magnificent due to its excellent condition.

Queen Mother Idia of Benin wears a crown of eleven small bearded faces (ten surviving) adorning her head. The small faces are inlaid with copper alloy which would have originally reflected warm reddish hues in their eyes and helmets. These stylized faces are symbols of the Portuguese traders and sailors that regularly visited the Kingdom of Benin. Their inclusion symbolizes the international trade and diplomatic relations that both Iy’oba Idia and Oba Esigie enjoyed with Portugal. These visiting Europeans were the African kingdom’s trading partners and political allies.

Below the European faces is an intricate pattern of hair. The hair is tightly twisted and forms an almost honeycomb pattern covering the upper half of Queen Mother Idia of Benin. It adds a geometric element to the natural features of the face, and it is strengthened by the clean hard lines of its edges across the forehead. The overall rendering is delicate but powerful, and it celebrates the natural beauty of afro-textured hair.

Below the patterned hair are two strong incisions inlaid with iron. They frame the four scar marks above each of the eyes. In 16th century Benin, as in many modern cultures today, scarification is socially accepted and valued. Similarly to tattoos, they are valued by many as permanent body art enhancing its wearer. However, unlike tattoos, scarification in 16th-century Benin was only allowed for warriors because it symbolized bravery and strength. Therefore, the scarification of Queen Mother Idia of Benin not only adds interest to her face, but it also declares her military experience and inner character.

Further below the scarification are the subject’s large eyes. They are wide, heavy-lidded, and almond-shaped. Like the two incisions, the eyes are inlaid with iron too. The pupils, now missing, were originally solid round circles of iron. Both eyelids were also originally inlaid with iron, and when black and polished, would have resembled the famous kohl eyeliner found in ancient Egypt. In its original condition, the black inlays against the white flesh would have dramatically contrasted and heightened the mask’s elegance.

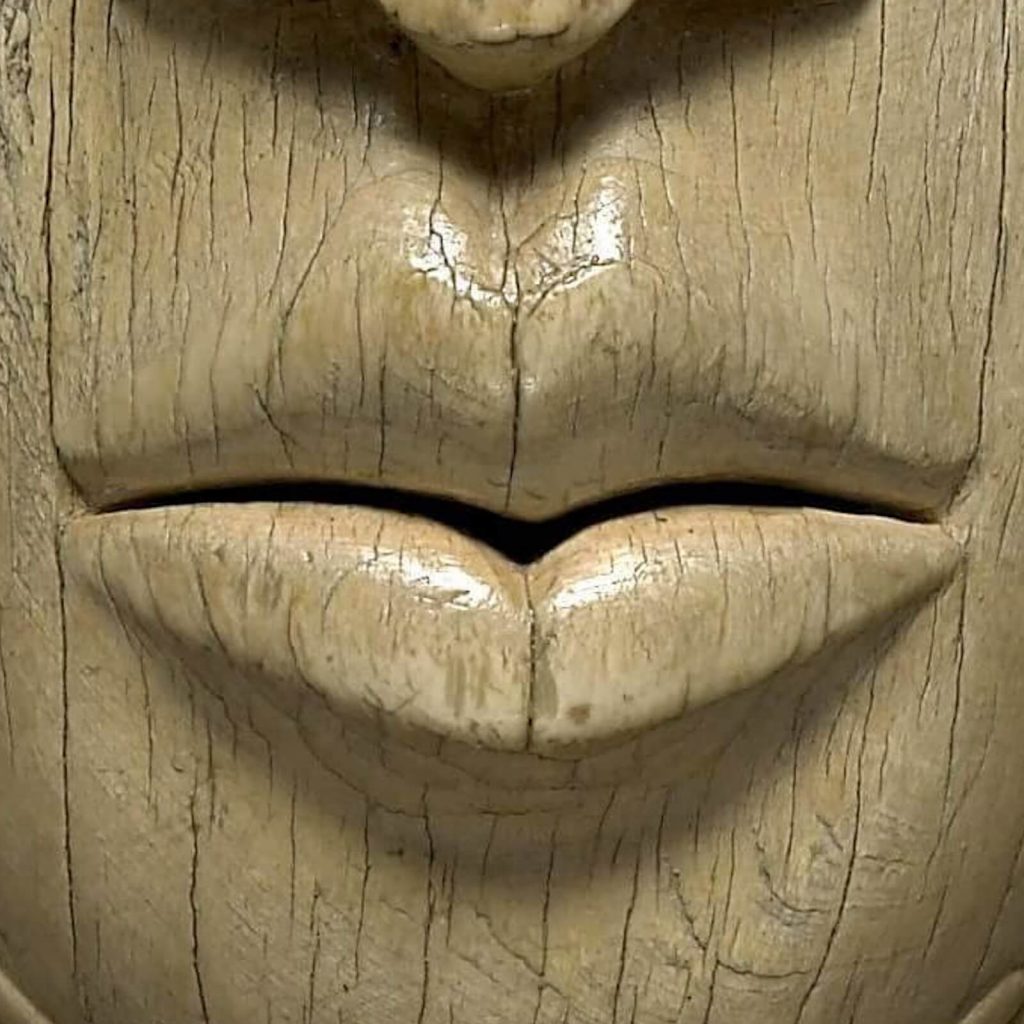

At the base of Queen Mother Idia of Benin is a marvelously carved lattice ruffle. It forms a luxurious collar around the face, neck, and suggested shoulders. Upon closer inspection, it too was inlaid with both copper and iron to form an interwoven pattern. The drilled holes between the metal elements add a greater sense of realism to the fretwork by allowing background light to glimmer through.

It cannot be denied that Queen Mother Idia of Benin is a gorgeous and powerful symbol of a mighty African queen and her kingdom. In many African communities, it is common practice to honor ancestors and elevate rulers to sacred status. This practice projects shared core beliefs that tie the present with the past and the ephemeral with the eternal. These beliefs are immortalized and preserved through the use of durable materials like terracotta, ivory, and cast metal in African art traditions. Queen Mother Idia of Benin has two of these three most durable African materials. Therefore, like this work, the art, architecture, and regalia of African royalty are commonly produced to project long-term wealth and power. It is primarily made by the finest artists from the finest materials. These practices are almost universally executed and place African art, especially royally commissioned African art, on par with Western art.

What is so sad is how this masterpiece found its way to the British Museum. This beautiful ivory piece, fashioned from an African material of abundance and prosperity, was stolen from the Royal Palace of Oba of Benin during the Punitive Benin Expedition of 1897. This British invasion not only stole priceless artwork and deprived modern Africa of its artistic heritage, but it also deposed Oba Ovonramwen Nogbaisiand and massacred many of his people. The Benin economy that once funded the creation of beautiful objects like this one was destroyed. The exportation of pepper, textiles, and ivory ceased, the Oba was exiled, and vast populations were killed. However, despite this tragedy and injustice, the kingdom’s legacy did not die.

The loss of Queen Mother Idia of Benin to a European collection does not deny the historical importance and artistic legacy found in the Kingdom of Benin. Modern Nigeria, the location of the former Kingdom of Benin, continues to revere its great past. They are proud of their heritage and their art. While Queen Mother Idia of Benin is no longer in-situ, its location does not diminish its grandeur and glory. It represents African ancestry, history, customs, culture, and fashion. Queen Mother Idia of Benin is now a cultural ambassador to the United Kingdom and the general Western world. May her ambassadorship promote and advocate a reevaluation of Africa’s noble legacy to the world and the world’s ignoble treatment of Africa.

H. Gardner, F. S. Kleiner, and C. J. Mamiya: Gardner’s Art Through the Ages. 12th ed. Belmont, CA 2005.

“Ivory Mask:” Google Arts & Culture. Accessed 13 Jun 2021.

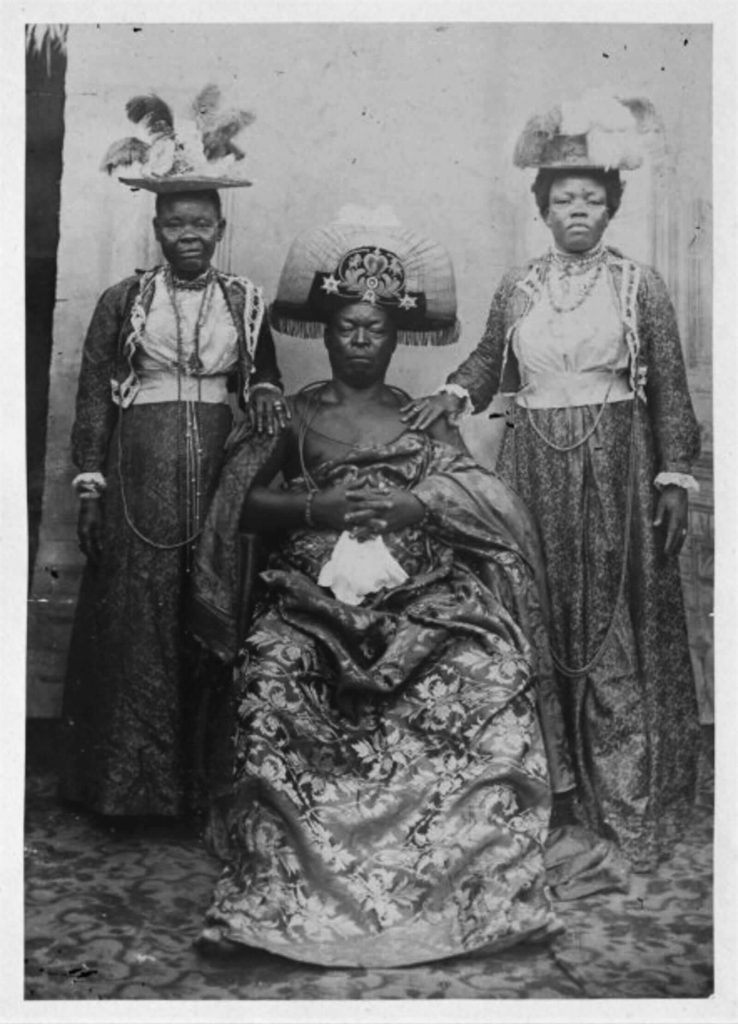

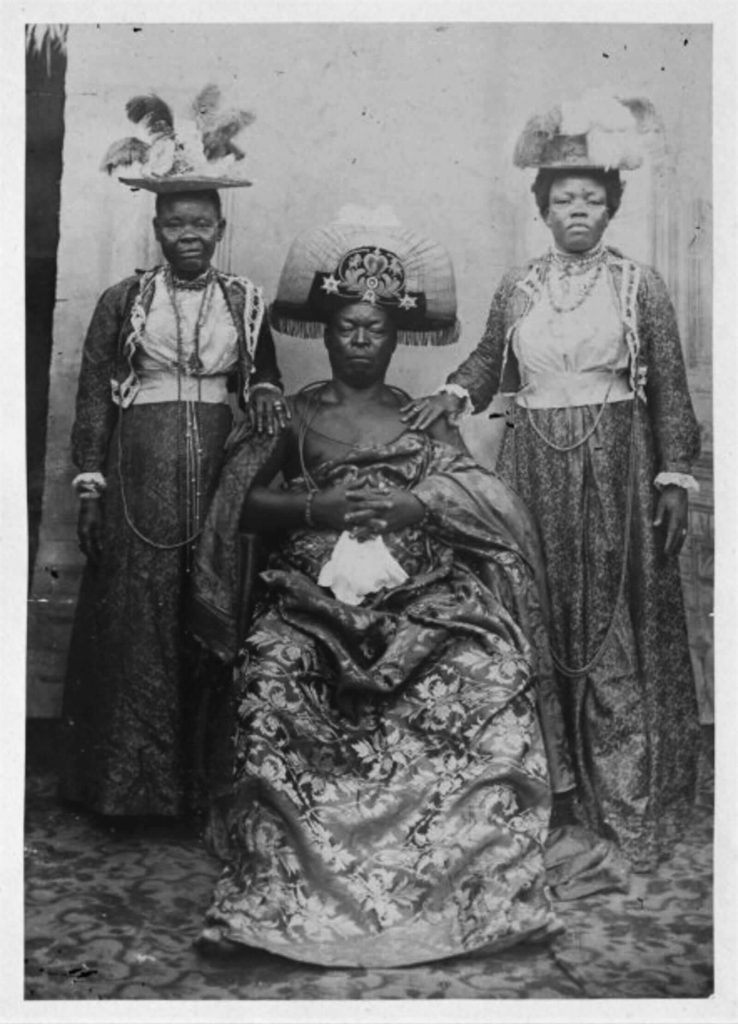

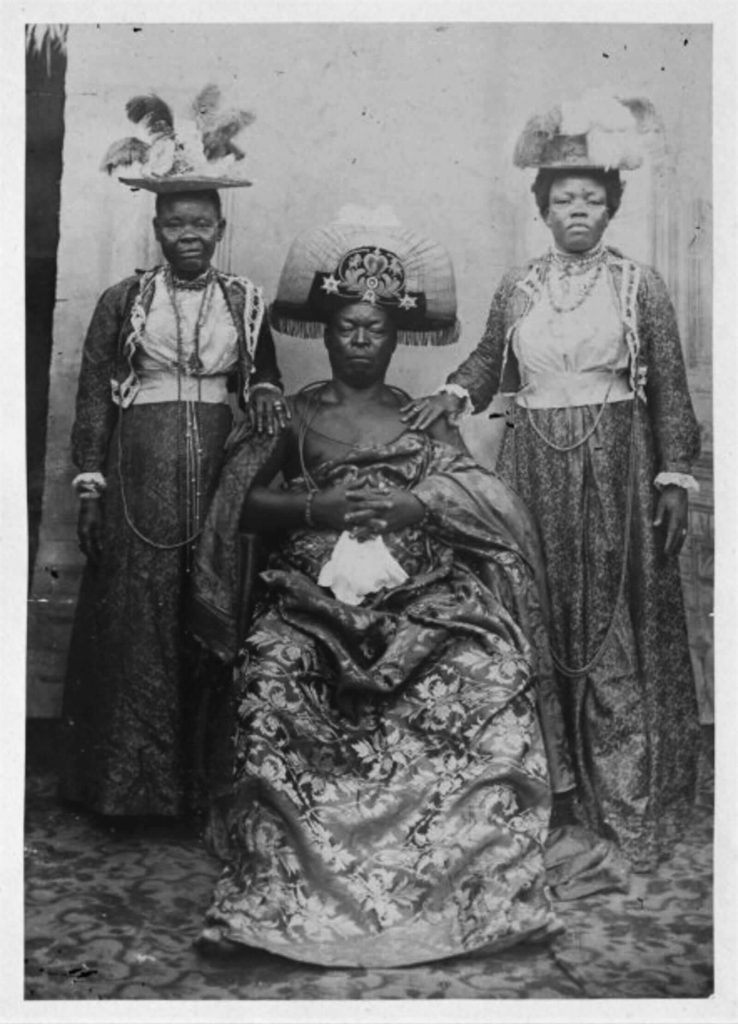

C. T. Lawrence: Obaski and Wives in Exile at Calabar. Photograph. London, 1910-1911. National Archives. CO 1069/64 P34.

“Pendant Mask:” Collection. British Museum. Accessed 13 Jun 2021.

“Queen Mother Pendant Mask: Iyoba:” Collection. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed 13 Jun 2021.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!