Discover 9 Indian Landscapes Through Modernist Lens

India’s rich and diverse topography has served as inspiration for artists throughout time. With awe-inspiring sites and landforms ranging from...

Guest Profile 4 July 2024

Virginia Elisabetta Luisa Antonietta Teresa Maria Oldoini – in short, Countess of Castiglione – was a real celebrity of her times. I imagine that in our times she would be someone as famous as Kim K., or at least as some super popular fashion blogger. Do you think you’ve never heard of her? In the 19th century, she was a very significant figure in the early history of photography. For 40 years she directed the photographer Pierre-Louis Pierson to create 700 photographs of her. Actually, she could be named the vainest queen of selfies.

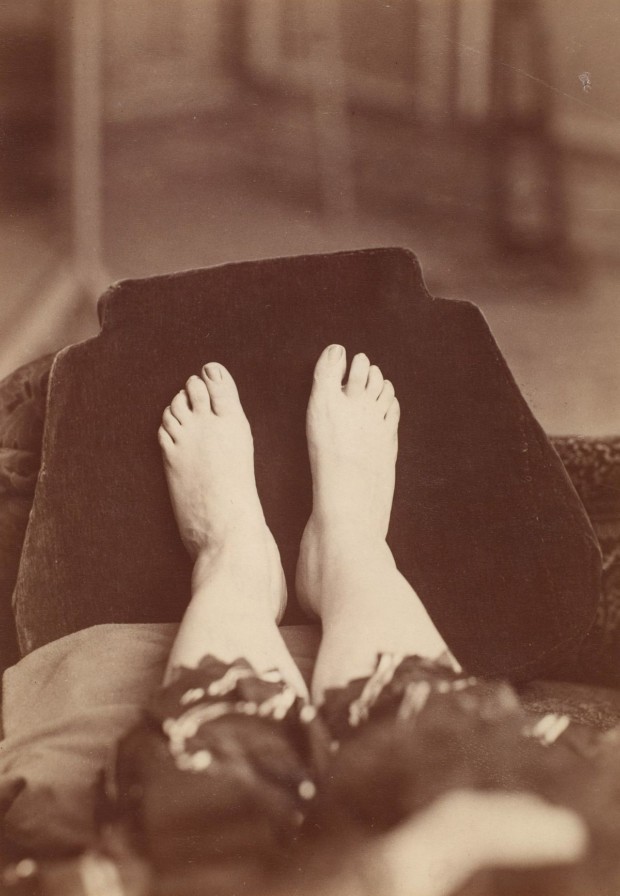

When I first saw this photograph I was at a loss for words. It was taken around 1863.

Virginia Oldoini was born in 1837 to an aristocratic family from La Spezia, Italy, and is now remembered among photography historians as the subject of 700 different photographs of Pierre-Louis Pierson in which she re-created the signature moments of her life for the camera. Yes, she created them, not the photographer. She acted as a producer and art director of the photoshoots.

When the Oldoini was 17, she married Francesco Verasis, Count of Castiglione. He was 12 years her senior. They had a son, Giorgio.

Virginia Oldoini’s cousin Camillo, Count of Cavour, was a minister to Victor Emmanuel II, king of Sardinia (that included Piedmont and Savoy). When the Count and Countess traveled to Paris in 1855, she was under her cousin’s instructions and Oldoini became a special agent for the cause of Italian unification. She achieved notoriety by becoming Napoleon III’s mistress. Of course, it was a scandal that led her husband to demand a marital separation. During her relationship with the French emperor in 1856 and 1857, she entered the social circle of European royalty and became a star.

The Countess was known for her beauty and her flamboyant entrances in elaborate dresses at the imperial court. She was losing a fortune for dresses and costumes. She was described as having long, wavy blonde hair, pale skin, a delicate oval face, and eyes that constantly changed color from green to an extraordinary blue violet.

In 1856 she began sitting for Mayer and Pierson, two photographers favored by the French imperial court. For the next 40 years, she directed Pierre-Louis Pierson to help her create 700 different photographs. She spent a large part of her personal fortune and even went into debt to execute this massive project.

Virginia Oldoini was a very conscious model. Most of the photographs depict the Countess in her theatrical outfits, such as the famous Queen of Hearts dress. She portrayed herself as various biblical and literary characters such as Beatrix, Salambo, Medea, Lady Macbeth, Judith, a nun, a prostitute, Anne Boleyn, Queen of Etruria, Queen of Hearts, and even a corpse in a coffin.

A number of photographs depict her in poses that were risqué for her era – notably, images that expose her bare legs and feet (!). In these photos, her head is cropped out.

The end of Virginia Oldoini was quite sad. She spent her declining years in an apartment in the Place Vendôme, where she had the rooms decorated in funeral black, the blinds kept drawn, and mirrors banished apparently so she would not have to confront her advancing age and loss of beauty. She would only leave the apartment at night.

In the 1890s she began a brief collaboration with Pierson again, though her later photographs clearly show her loss of any critical judgment, possibly due to her growing mental instability. She wished to set up an exhibit of her photographs at the Exposition Universelle (1900) titled The Most Beautiful Woman of the Century, but this did not happen. On November 28, 1899, she died at age 62 and was buried at the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

Robert de Montesquiou, a Symbolist poet, dandy, and avid art collector, was fascinated by Countess di Castiglione. He spent 13 years writing a biography, La Divine Comtesse, which appeared in 1913. After her death, he collected 433 of her photographs, all of which entered the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!