Masterpiece Story: Self-Portrait by Faith Ringgold

Self-Portrait by Faith Ringgold is a masterpiece of 1960s portraiture, feminist art, and Black...

James W Singer, 3 November 2024

3 November 2024 min Read

In the discourse on the Black presence in Western history, it is taken for granted that Africans in art represented solely enslaved people, and their image was associated with humiliation and submission. Is it really that simple? In 1661, Rembrandt painted an intimate study of two African men, presumably brothers, in which he managed to depict their individuality free from stereotypical assumptions. Let’s delve into the history behind this masterpiece.

The Dutch Golden Age, a period in Dutch history when Rembrandt lived and worked, is commonly perceived as an exclusively European phenomenon, but the archival studies reveal.1 that the population of the Netherlands was not at all homogenous. Just like today, Amsterdam was also highly diverse and international during the late 16th and throughout the 17th century.

A small community of free Black people formed in the period 1620–1670 along the Jodenbreestraat in Amsterdam, which happened to be the place where Rembrandt resided. However, this fact has been omitted or hardly mentioned in the art historical scholarship on the African presence in early modern Europe. It, therefore, deserves more attention than received so far.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Two African Men, 1661, Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands.

Rembrandt van Rijn is known today as the most important and influential artist in Dutch history. His works are reproduced for commercial use in millions of copies on objects of everyday use, such as t-shirts, teacups, and smartphone cases. He became the ultimate symbol of Dutch culture, history, and tourism. Probably, all of you have seen at least once The Night Watch or the Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, but have you ever seen The Two African Men?

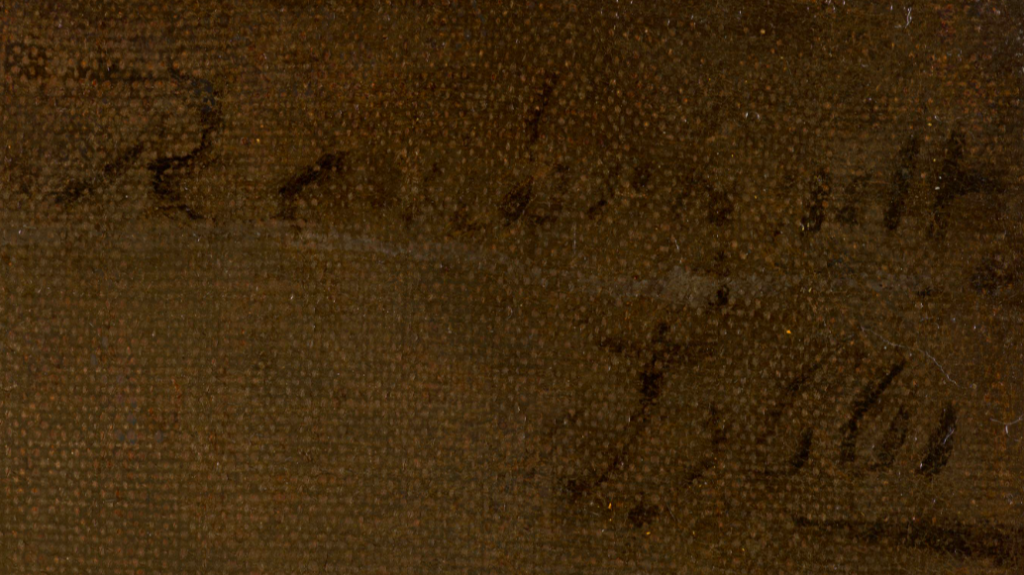

Rembrandt van Rijn, Two African Men, Rembrandt’s signature, 1661, Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands. Detail.

Frontal façade of Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands. Photo by Ivo Hoekstra/The New York Times.

This remarkable painting hangs today at the Mauritshuis in The Hague, an art museum that houses Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring. Additionally, it was a former residence of Count Johan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen, a German humanist prince and art collector, but also the governor-general of Dutch Brazil and the initiator of the Dutch slave trade. Today, the museum endeavors to revisit the troubled past of its original owner.

Pieter Nason, Count Johan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen as the Grandmaster of the Knights of Malta, c. 1666, National Museum in Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland.

Rembrandt painted African sitters (probably neighbors) on several occasions, but The Two African Men are considered his most important depiction of Black people. It is important to stress that this work is not a portrait but a tronie, a genre developed exclusively in Dutch and Flemish art of the 16th and 17th centuries, serving as a bust-length physiognomical study of a “typical” human character. This tronie, however, is not so typical for this genre. As mentioned in the introduction, the Two African Men reveal some traces of individuality, but they are placed in a context of a study.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Two African Men, 1661, Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands. Detail.

He captured the men in an intimate and informal moment, revealing the proximity between the two. They could have been brothers or relatives. Rembrandt presented them without conventional oriental attributes, such as instruments, bows, turbans, or earrings. The frontal figure, however, is stylized clearly in the manner of Roman portrait busts.

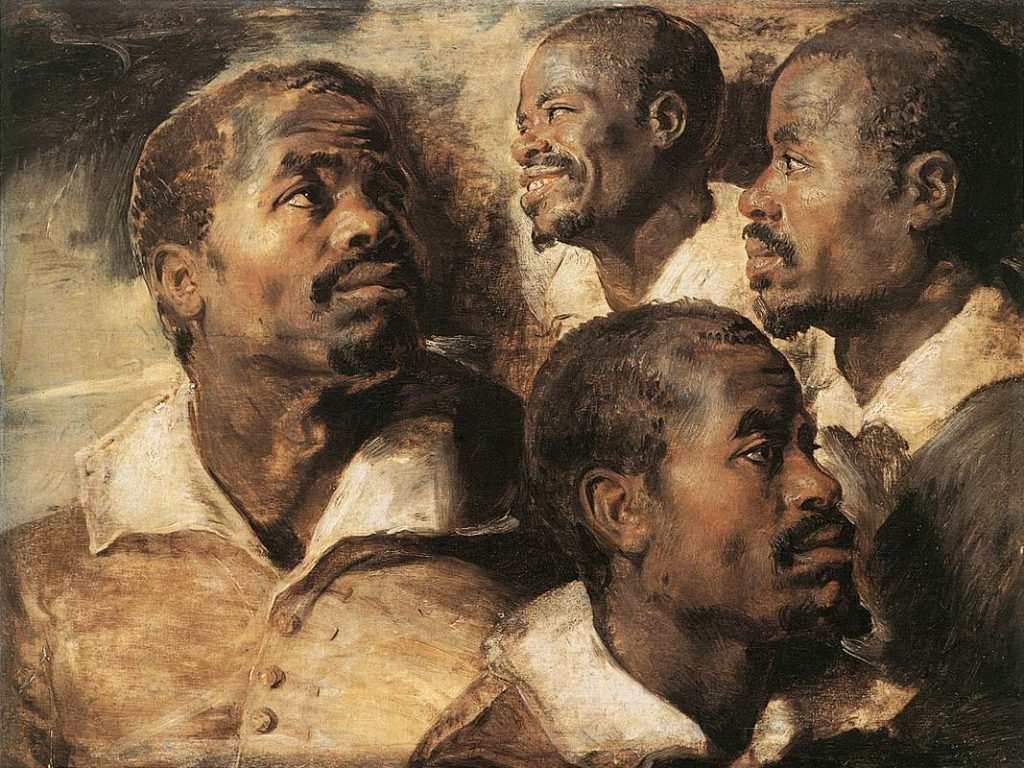

Previously, the men were thought to be two head studies of one person, as seen in head studies by Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens from around 1615.

Peter Paul Rubens, Four Head Studies of a Black Man, c. 1615, Royal Museums of Fine Art of Belgium, Brussels, Belgium.

The man on the right stands straight with an animated face, looking upwards as if speaking to the man to the left. The man on the left is leaning forward, with his chin hanging over the arm of the other. He seems to be beset with thoughts, in a contemplative state, not even listening to the man by his side.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Two African Men, 1661, Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands. Detail.

Rembrandt could have presented the contrast between the two value systems of vita activa (active life) and vita contemplativa (contemplative life), frequently addressed by Renaissance philosophy and art.

Between the 1650s and 1660s, he focused more on “the subtle and quiet evocation of inner emotion” in observing people’s relationship to each other in cues or subtle expressions, as we see in The Jewish Bride, painted around 1665, rather than in direct interactions, as in The Night Watch, painted over twenty years earlier.2

Left: Rembrandt van Rijn, The Jewish Bride (also known as Isaac and Rebecca), c. 1665–c. 1669, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Detail; Right: The Night Watch, 1642, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Detail.

In Two African Men, Rembrandt also indicated an emotional relationship between the two models. Scholars suggest that this tronie reveals similar physical proximity as seen in depictions of siblings in Dutch family portraits. Due to the unconventional form of this figure study, it is not clear what was the exact purpose of the painting.

According to David de Witt, the tronie could have served as “an element of artistic performance, for the connoisseurs Rembrandt often had in mind during his late period.”3 Elmer Kolfin, on the other hand, presents a more practical explanation, that being that the Two African Men could have served as a model of dark skin’s tonal study for Rembrandt’s pupils.4

The identities of the two models are impossible to establish, as no extant documents or bills link this painting to specific individuals. Such is the case with almost all portraits of Black people from the 16th and 17th centuries painted in the Netherlands since individual portraits of Black sitters in Netherlandish art were extremely rare but not nonexistent.

Mark Ponte. “‘Al de swarten die hier ter stede comen’ Een Afro-Atlantische gemeenschap in zeventiende-eeuws Amsterdam.” Tijdschrift voor Sociale en Economische Geschiedenis/The Low Countries Journal of Social and Economic History 15, no. 4 (2019): 33–61.

David de Witt. “The Black Presence in the Art of Rembrandt and His Circle.” In Here. Black in Rembrandt’s Time, by Elmer Kolfin and Epco Runia, 89–119. Zwolle: WBOOKS & Het Museum Rembrandthuis, 2020, p. 113.

David de Witt. “The Black Presence in the Art of Rembrandt and His Circle.” In Here. Black in Rembrandt’s Time, by Elmer Kolfin and Epco Runia, 89–119. Zwolle: WBOOKS & Het Museum Rembrandthuis, 2020, p. 115.

Elmer Kolfin. “Rembrandt’s Africans.” In The Image of the Black in Western Art, Volume III: From the “Age of Discovery” to the Age of Abolition, Part 1: Artists of the Renaissance and Baroque, edited by David Bindman and Henry Louis Jr. Gates, III: 271–306. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010, p. 298.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!