Akhenaten: Artistic Development in the Amarna Period

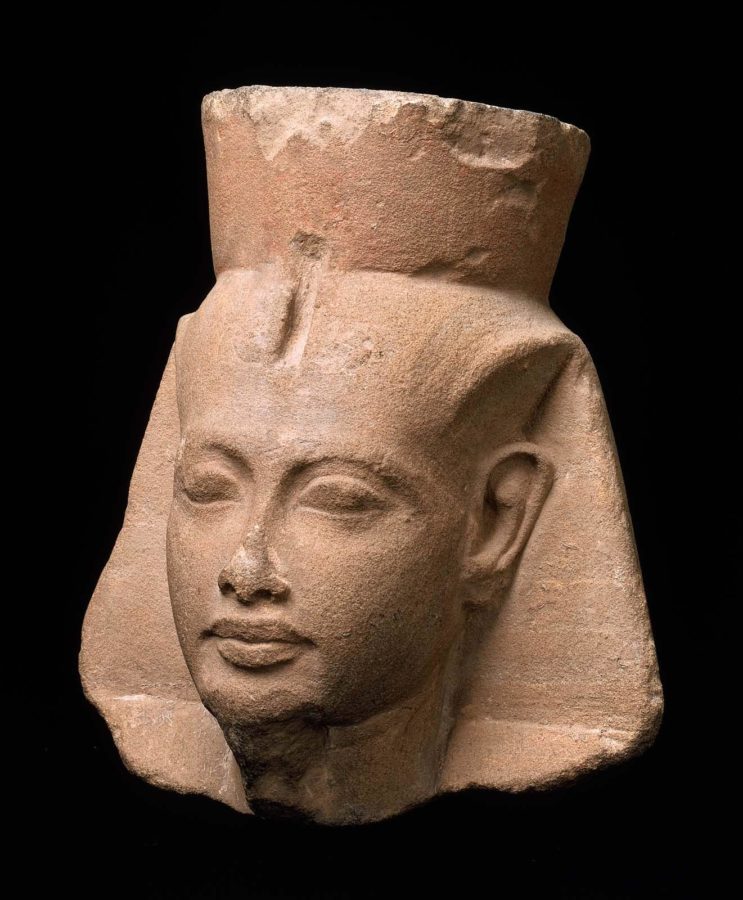

Amenhotep IV, widely recognized as the notorious Akhenaten, was the enigmatic “heretic” pharaoh who ruled during the Eighteenth Dynasty.

Maya M. Tola 20 July 2023

Nefertiti is a beauty icon and one of the most powerful women who has inspired us throughout centuries. Responding to the rhythms of the age, she seized the opportunities of her time. But Nefertiti also left us with many mysteries. And we continue to wonder: Did her power and beauty drive changes in art? Or did the changes in art make Nefertiti beautiful? What does her beauty mean for us? Owing to skilled artists, we can now look at her life through the lens of art.

Nefertiti (c. 1370-1330 BCE) was an Egyptian queen and the Great Royal Wife of Akhenaten, an Egyptian pharaoh. She lived in a country rich with history and tradition. In about 3150 BCE, King Menes unified Egypt. For the next three millennia Egyptian culture flourished. It remained distinctively Egyptian in its religion, arts, language, and customs.

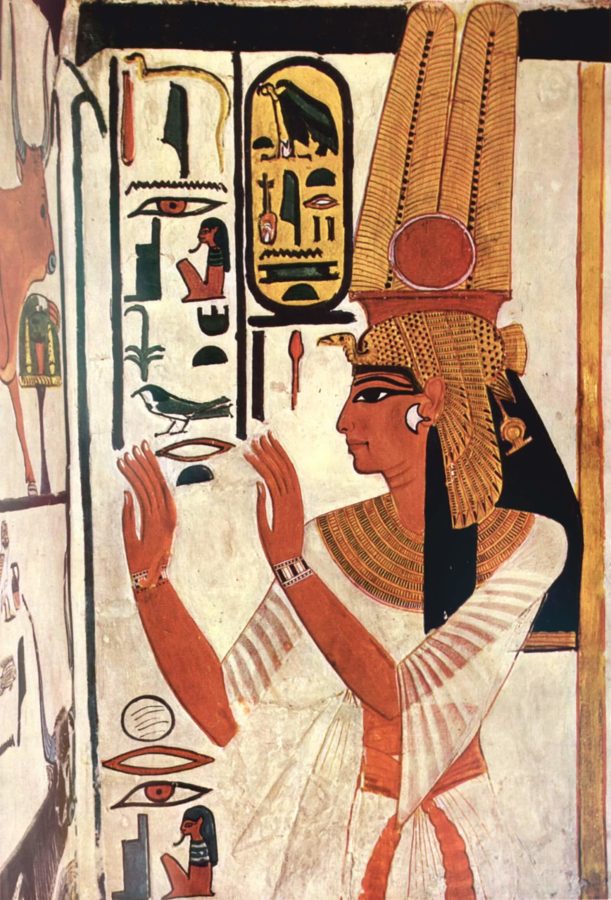

Egyptian art rarely belonged to the moment. It illustrated and invoked what is eternal. Artworks served religious and ideological purposes. Artists depicted a ruler as an archetype. They could help a pharaoh to legitimize its rule. As a result the Egyptian iconography remained recognizable throughout many dynasties.

Knowing this conservative style, we can immediately visualize an Egyptian human figure. Artists depicted it as a composite. They showed the head in profile, but the eye appeared from the front. Furthermore, to create a specific shape, craftsmen accentuated unnaturally large eyes with eyeliner. Usually, it represented a hieroglyph meaning the word “beauty.”

Ancient Egyptian art also had the tradition of “frontality”. In other words, royal and divine subjects faced straight ahead without any noticeable bending or turning of the head or body. This allowed the stone statues to develop a static dignity.

We separate Ancient Egypt into kingdoms with intermediate periods between each kingdom. Each dynasty has its number. For example, Nefertiti, the beauty icon, and her husband Amenhotep IV (c. 1353-1336 BCE), later known as Akhenaten, lived during the reign of the 18th Dynasty. It is the first dynasty of the New Kingdom. In this era, ancient Egypt achieved the peak of its power.

Nefertiti, a beauty icon and mysterious queen, was born at this height of Egyptian culture in about 1370 BCE. We are not certain about the details of Nefertiti’s birth. However, her story started with wealth and excess. Nefertiti means “the beautiful one has come”. She may have been the daughter of a high government official, Ay. Some think that Ay was possibly her husband’s uncle.

Ay may have also acted as a tutor to the crown prince Amenhotep IV who later became an Egyptian pharaoh. Using his position of power, Ay must have placed Nefertiti as Amenhotep’s Great Royal Wife. She was effectively the king’s deputy. In the case of her husband’s death, Nefertiti would rule Egypt until the next king was able to take his place on the throne. In addition to her political role, she represented all of Egypt’s women before the gods. Through her proximity to a divine king, she would become divine herself.

Amenhotep IV and Nefertiti ruled first in Thebes, and then for about 12 more years from the city of Akhetaten, modern-day Amarna. As a product of the court Egyptian culture, she was probably a great politician. She knew how to lower her eyes with grace, when to make eye contact, and when to do what the sun king ordered. Thus, she prepared herself to stand among women rulers.

As for Amenhotep IV, people knew what to expect of their divine leader. He would maintain the traditional rituals as the chief priest to make sure the Nile crested and receded seasonally. By the late 18th dynasty, there were at least 1,000 deities whose individual characters make them impossible to count.

These gods both controlled Egypt and offered the chance of continued life beyond death. We might recognize some gods such as Osiris, the god of life, death, and fertility. His wife is Isis or the goddess of the throne. Their son, Horus, is the god who allowed pharaohs to become godlike, while his brother, Set, is the god of the desert.

The three solid gold figures represent Osiris, surrounded by his son, Horus, and his wife, Isis. Horus and Isis extend their hands toward their father and husband’s shoulder in a protective gesture. These gods are recognizable by their attributes.

For example, Osiris has a feathered tiara and shroud. Horus is adorned in a falcon head and double royal crown. In imitation of the goddess, Hathor, Isis wears a horned disk. Osiris is crouching on a pillar of a deep blue lapis lazuli that places him at the same level as his family. Artists fashioned the palm leaves on the cornice and the base in gold cloisonne inlaid with lapis and red glass.

When Amenhotep IV came to the throne, the most powerful god of all was Amen. This god was an ancient Theban deity. Pharaoh’s ancestors had vied with each other to make increasingly splendid improvements to Amen’s Karnak Temple. They also created a royal cemetery in the Valley of the Kings to link the 18th Dynasty kings forever with Amen. Then, why did this particular pharaoh destroy the order of things?

To realize his vision, the pharaoh first deleted the name of Amen from all inscriptions. He emptied the traditional temples, enraging the priests. Then, he moved his court downriver from Thebes to present-day Amarna, a site that the pharaoh named Akhetaten.

The Aten was the disc of the sun and originally an aspect of the god Ra. Moreover, the god was the creator and giver of life. The pharaoh took a new name Akhenaten or “Horizon of the Aten”, claiming to be the sole prophet of Aten. To him alone did the god reveal himself.

Moreover, painters and sculptors began to represent Akhenaten’s god neither in animal nor in human form. Artists also chose not to depict composite human-animal form. They simply showed the god as the sun disk emitting life-giving rays.

This was a major break with tradition. The new practice may have been an attempt to strip the existing priesthoods of their wealth and power by channeling all worship through the throne. Not only did Akhenaten’s god represent the power of the sun, but he and his immediate family might also have been living gods.

Nefertiti supported Akhenaten’s new religious cult. She was her husband’s chief priestess and ideological muse. Soon artists proceeded to create a sunken relief for Akhenaten. In this technique, the sculptor chisels deep outlines below the stone’s surface instead of cutting back the stone around the figures to make them project from the surface. The relief reveals the androgynous Akhenaten, his wife, and three of their six daughters basking in the rays of Aten, the sun disk, which end in hands holding the ankh, the sign of life.

We can see that Akhenaten lifts one of his daughters to kiss her. Another daughter sits on Nefertiti’s lap and gestures toward her father. Meanwhile the youngest daughter reaches out to touch a pendant on her mother’s crown. Artists depicted the royal couple with the elongation of visage and limbs. Their chins pulled down in a decidedly animalistic manner. The solar orb rises behind the pharaoh and Nefertiti, deforming and elongating their forms.

At its most dramatic, it might have seemed that sunlight was even shooting from their extremities and from the tops of their crowns. Perhaps, Akhenaten’s artists tried to formulate a new androgynous image of the pharaoh as he was the child and image of Aten on earth, the sexless sun disk.

This kind of realism was not typical for Egypt. Yet, it typifies the radical upheaval that accompanied Akhenaten’s new religious cult. The depiction of royalty previously was rigid and formal. Akhenaten introduced intimate family scenes into the art. He was more relaxed in showing his relatives. Thus, we see the transition from rigid forms to exaggerated images.

Both Akhenaten and Nefertiti knew that times inevitably change. They may have wanted to hold onto power and continue their dynasty. With their daughters, however, they needed a plan to ensure a succession of the rule. Although Nefertiti’s name disappears from historical records, she could have still ruled under the name of Neferneferuaten after her husband’s death.

As an alternative, Nefertiti, the beauty icon could have disguised herself as a male and assumed the male alter-ego of a ruler Smenkhkare. If this was the case, she could have elevated her daughter Meritaten to the role of Great Royal Wife. Nevertheless, Smenkhkare might also have been a half-brother or a son to Akhenaten.

One of Smenkhkare’s directives was to abandon the city of Akhetaten. Thebes became an administrative center. It was probably a reconciliation effort to atone for the changes of religion. This measure would retain the goodwill of the people. Smenkhkare may have reinstalled the familiar faces of gods like Amun, Mut, and Khonsu.

The pharaohs who followed Akhenaten continued to reestablish the Theban cult and priesthood of Amen at Karnak, restoring Amen’s temples and inscriptions. They managed to revert Akhenaten’s brief change of cult, and largely abandoned the city that Akhenaten built. After Smenkhkare and Neferneferuaten, the 18th dynasty concluded with Tutankhamen, Ay, and Horemheb.

Succeeding to the throne as a boy, the clergy used Tutankhamen to repudiate Akhenaten’s religious reforms. However, later rulers continued to associate him with Akhenaten. Tutankhamen’s memory was suppressed and his statues were appropriated by other rulers, notably Horemheb.

In contrast, Nefertiti may have been innovative in her approach to forming alliances. Suppiluliuma I (reigned c. 1344-1322 BCE) was a king of the Hittites. Once he received a letter from the Egyptian queen. She asked the ruler to marry one of the king’s sons. This request was unusual as New Kingdom royal women did not marry foreign royalty. Nevertheless, the king missed his chance to bring Egypt into his empire.

The writings and paintings found on walls, shards of pottery, and tombs in the Amarna provide clues to Nefertiti’s life. However, the words and pictures of her cease abruptly near the end of her husband’s reign. Therefore researchers could not piece together any reliably accurate histories of Nefertiti. Did she leave Amarna voluntarily? Was she killed? Did she go into hiding and then resurface after her husband died? And did she then rule in his place?

Nefertiti might have gone into oblivion. However, in 1912, an expedition directed by a German Egyptologist, Ludwig Borchardt (1863-1938), was excavating the ancient city of Amarna. He found the sculptor Thutmose’s ruined house and studio complex. Thutmose was “the pharaoh’s favorite and master of works”.

Among the recovered items at the master’s studio was the polychrome Nefertiti bust. It is made of a limestone core, covered with painted stucco layers. Ludwig Borchardt took the sculpture to Germany. As a result, the finds from the site still draw crowds to Berlin’s Neues Museum. Thanks to the Ancient artist, Nefertiti appears attractive and refined. The bust might have been a master study for others to copy. Despite this fact, Nefertiti, the beauty icon, does not lose her good looks.

When we notice the missing left eye, we may think that the inlay has simply been lost. We tend to ignore this eye and simply complete the image in our minds. Wanting to create a story for ourselves, we even assume that Nefertiti had a cataract or some sort of deformity.

At the same time, the sculptor adjusted the proportions of her head and neck to meet the era’s standard of spiritual beauty. The Nefertiti’s tall crown is dark blue, with a uraeus or cobra rearing over the forehead, and a multicolored band or ribbon circling the crown and tying at the back. Two colorful ribbons hung from the nape of the neck.

The enduring fame of the bust adds to the representation of Nefertiti. Her face continued to evolve throughout her husband’s reign. The long nose, square jawline, and strong chin contribute to a striking portrait of a woman who processes masculine characteristics. The Queen’s likeness operates between the realms of the masculine and feminine. The merging features create a hybrid face that is both captivating and unsettling.

The Nefertiti bust fitted perfectly with the colorful, geometric art deco style that was starting to represent post-war opulence and glamour. A contemporary sculptor could have created it. Yet, it was a sculptor who had lived and died several thousands of years earlier made this Nefertiti.

The bust has a contemporary feel to it and continues to inspire modern artists. For example, in 1993 American artist Fred Wilson created five plaster replicas of the Berlin bust. He painted his artwork in various shades of skin tone ranging from beige to dark brown. The five identical but differently colored Nefertitis let you think about the racial identity of the ancient Egyptians.

Swayed by the bust, some people believe that Nefertiti was “white”. At the same time, others think that Nefertiti might have been “black”. As for ancient Egyptians, skin color was irrelevant. Behavior was what mattered. They divided their world by customs, into Egyptians and non-Egyptians.

Based on tradition, Egyptian artists represented men with red-brown skin. They gave females yellow-white skin. This made an easy distinction between males and females of all ages. However, it was a convention rather than a rule. For example, a woman from Akhetaten might have red-brown skin. The Berlin bust has a pinkish-brown skin tone. Still, it tells us nothing about Nefertiti’s actual skin color.

Why do many people think that the Nefertiti bust is a portrait of a beautiful woman? Delicate features, the long graceful neck, and an expression of gentleness can make up a royal lady. The bust also lacks the representation of hair. Nefertiti may have either shaved her head or tucked her hair up, inside her crown. The merging features associated with both sexes create a hybrid face that is both captivating and unsettling.

The Berlin Nefertiti has a symmetrical face. Usually, we find these kinds of faces attractive. Does she appear remote and artificial? She might be just an imaginary ideal. Nevertheless, she remains pleasing to the eye. This version of Nefertiti has harmony in her.

Nefertiti is still a popular subject at parties and in fashion magazines. Many women draw inspiration from the bust by choosing Egyptian-style makeup and costumes. They can take photographs with their hair swept back. Sometimes, we compare conventional beauties to the bust.

At the same time, we tend to forget that beauty is only skin deep. There are also several less attractive versions of Nefertiti. But we are willing to accept that the Berlin bust is the true likeness of the queen. Why is this bust of Nefertiti so beautiful to so many of us, irrespective of age, gender, race, or culture?

Perhaps, her power as a co-ruler transformed the power of the image. Looking at the beautiful Nefertiti, we want to un-riddle the story of her life. Was she the sole ruler after her husband’s death? Did she try to restore traditions? We may never know for sure. But things that motivated Nefertiti and her husband bore the art that continues to inspire us throughout generations.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!