Akhenaten: Artistic Development in the Amarna Period

Amenhotep IV, widely recognized as the notorious Akhenaten, was the enigmatic “heretic” pharaoh who ruled during the Eighteenth Dynasty.

Maya M. Tola 20 July 2023

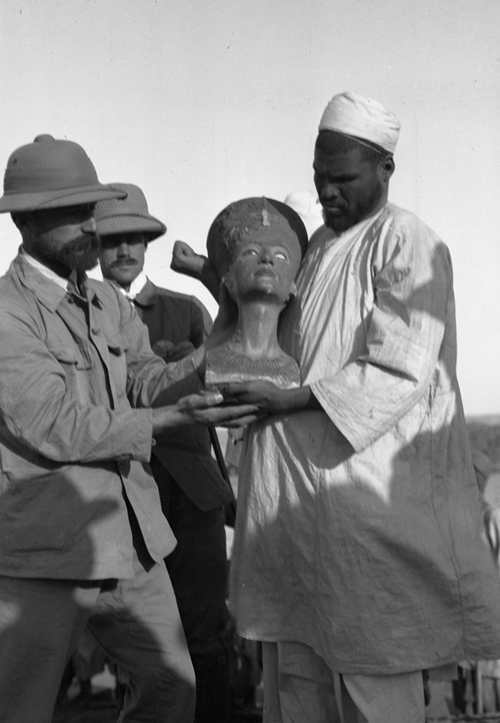

On December 6, 1912, a team of excavators from the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft, led by Ludwig Borchardt, unearthed a wonderful work of art. They found the bust of the Egyptian queen Nefertiti in the workshop of Thutmes, the sculptor of the Pharaoh Akhenaten, on the site of Amarna, in Middle Egypt. This sculpture soon became an icon of femininity, radiating around the world. That is, until Swiss journalist Henri Stierlin investigated and threw a stone in the proverbial still pond. His book, The Bust of Nefertiti: A Sham of Egyptology? published in 2009, proclaimed loud and clear that one of the masterpieces of Egyptian art was, in fact, a hoax.

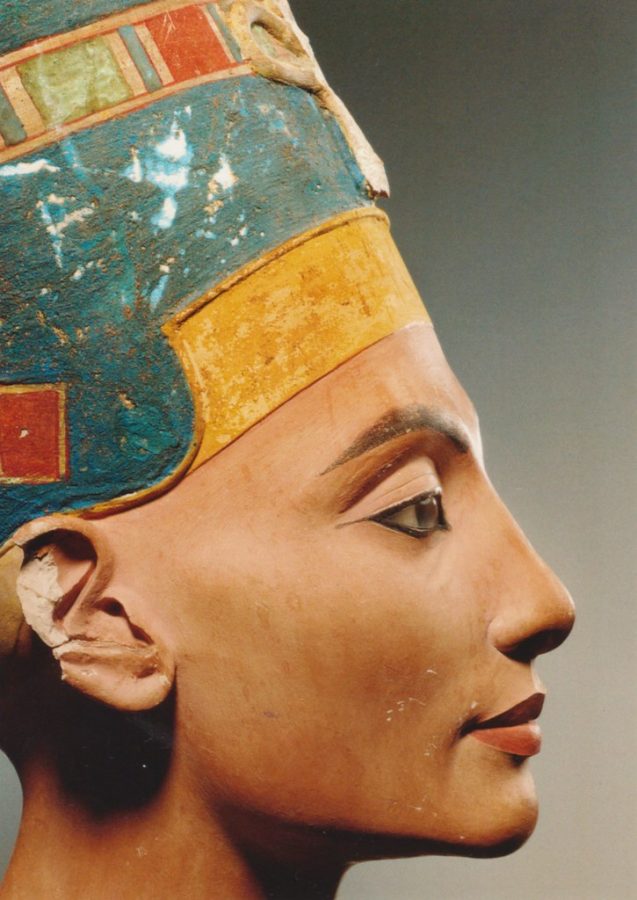

To admire the bust of Nefertiti at the Neues Museum in Berlin is to be a spectator of Egyptian art at the height of its stylistic peak. The sculpture shows a young woman with a harmonious face, whose purity of facial lines is emphasized by elegant make-up. This gentle face is that of the illustrious Queen Nefertiti, “Beauty has come,” who ruled ancient Egypt between approximately 1370 and 1333 BCE, alongside her no less famous royal husband, Akhenaten.

The leather helmet with metal reinforcements that she proudly wears leaves no doubt as to the identification of this beautiful woman; this is indeed her personal crown. This work seems to mark a turning point in the artistic style established by Akhenaten in correlation with the cult of the solar disk Aton.

Amarna art – named after Amarna, the current name of Akhenaten’s capital, – is characterized, from the early years of Pharaoh’s reign, by its aestheticizing play of curves and counter-curves. For some Egyptologists, this bust materializes the abandonment of this fluid and dynamic style in favor of softer lines, imbued with a certain formal perfection. The addition of layers of plaster discovered following careful analysis on the limestone structure goes also in this direction; the craftsman Thutmes – if he is indeed the author of the work – had only one watchword; the idealization of the figure of the queen.

From an object of contemplation, the bust of Nefertiti suddenly turned into an object of controversy. The scandal came mainly through the work of Henri Stierlin in The Bust of Nefertiti: A Sham of Egyptology? (Infolio, Gollion).

The writer thunders that the sculpture is in fact not ancient. According to him, during the excavations at the Amarna site, Borchardt’s team wanted to discover the manufacturing techniques of the Cursed King’s craftsmen. They had at their disposal an abundant stock of minerals necessary for the creation of pigments. Also, limestone was particularly obtainable on the site. It was therefore theoretically possible to create the bust from scratch. However, still according to the journalist, everything would have changed during the visit of the German Imperial Highnesses to Amarna. They would have seen the bust, forcing Borchardt and his family to invent a recent discovery with the royal guests.

Does that sound a bit far-fetched to you? In order to conclude on this hypothesis, Stierlin developed various arguments in his book.

The main disconcerting fact brought to light by the author is that there was no excavation report on the discovery, nor public exhibition before… 1923! What really happened on that day in December 1912? It is only reported that an object emerged from the sand of one of the rooms in Thutmes’s workshop. It is about the bust, fallen face down, almost intact – an element which did not fail to surprise the journalist, because another bust which fell in the same room was itself in a thousand pieces…

The published report in 1913 on the excavations of the workshop did not speak of the bust. However, a visit to the excavation site of Saxon Prince Johann Georg provided three similar photos of the bust. The photos were taken shortly after the discovery.

In reality, Ludwig Borchardt only explained the discovery and the object in 1923, while the first public exhibition of the bust only took place in Berlin… Until then, James Simon, a patron of Borchardt’s, kept the bust secretly.

Stierlin also found that the left eye is missing, while the ear cavity is perfectly clean and finished. Why didn’t the sculptor finish his work? Likewise, the vertical cut of the shoulders at first appears abnormal. In ancient Egypt, a bust rarely had the shoulders cut off, with very rare exceptions. However, this argument actually does not hold water. Indeed, in the context of a sculptor’s studio, it is quite likely that this cut is present, especially as it could allow the work to be embedded in a plinth. As for the missing eye, it is not uncommon for an Egyptian work not to be completed. If this bust is a model, this absence can be easily explained.

Henri Stierlin also put forward the surprising claim that Nefertiti’s bust is not in the Amarna style. However, German Egyptologist Rolf Krauss has highlighted the use of a proportion grid for the use of Amarna artisans. This analysis proves that the proportions of the face and the neck are not improvisations. Instead, they do indeed comply with the rules of Amarna art.

Finally, what to think of Henri Stierlin’s assertion? No argument seems really decisive. However, the journalist has the merit of raising various inaccuracies regarding this discovery. For example, the approximations of Borchardt, deemed precise and rigorous, as well as his desire not to exhibit this bust in public.

Nevertheless, everything suggests that this is a true ancient Egyptian work. In any case, this is the current opinion of the great majority of Egyptologists, such as Dominique Farout, philologist and professor at the Ecole du Louvre.

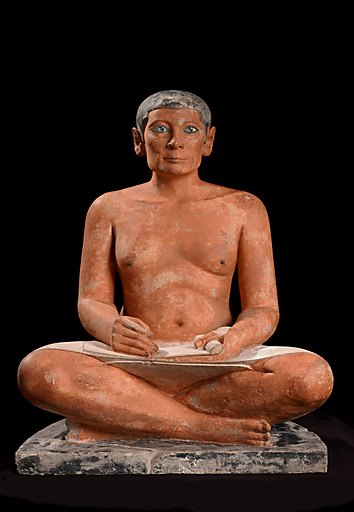

Keep in mind also that the stone, plaster, and pigments were tested and analyzed in 2013. They are authentic and correspond to the materials used in the time of Akhenaten. Nevertheless, it is impossible to date the production time of the object with the absence of plant debris. The debris is essential for a Carbon 14 analysis. Finally, note that the perfect conservation of the bust is far from being an exception. Archeologists have discovered many perfectly preserved Pharaonic statues; the “crouching scribe” of the Louvre Museum (Paris, France) can attest to this.

Closed case?

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!