11 Years of DailyArt Mobile App: Happy Birthday to Us!

As a fervent art enthusiast and tech aficionado, my journey with the DailyArt mobile app has been nothing short of transformative. Today, I’ll...

Zuzanna Stańska 19 August 2023

The feast day of All Souls and the festival of Halloween are celebrated close to each other in the Western calendar, but despite being closely associated with each other they are not the same holiday.

All Souls, or in the Anglican tradition The Commemoration of the Faithful Departed, is a Christian day of remembrance during which we remember and pray for the departed. We bring flowers, light candles, and spend time thinking about their influence on our own lives.

Halloween is rooted in the ancient Celtic tradition of Samhain which marked the end of summer. It was a time of tension between the realms of man and the gods during which propitiation was important to ward off the dangers of the coming winter season. They believed that the souls of the dead would come home, and often a place was set at the table to welcome them. They made offerings of food, slaughtered animals for food, and lit bonfires on hilltops to mimic the strength of the summer sun.

Even though these events are separate, the theme of death and rebirth is shared by both of them. All Souls celebrates the deaths of those we have known, and leads our thoughts towards rebirth in the afterlife; Samhain marked the end of summer and the beginning of winter and looked ahead to the rebirth of the land. The Celts may have liked the art of Giuseppe Arcimboldo, plus this would make a brilliant Halloween mask!

Because of Halloween and All Souls, we are more preoccupied with death at this time of the year. While life is certainly precious, it is our thoughts on death that consume us more. We see it as morbid and wrong and associate it with loss, pain, and fear, rather than anything positive. Our experiences and beliefs might account for our individual attitudes towards it. Have you lost someone you loved? Maybe you came close to death through an illness or an accident? Have you witnessed death in a terrible situation beyond your control? Have you been happily shielded from it because you’re young, or lucky? Do you believe in God? There are many ways to look at this and so many answers to any questions that we might ask.

The only certainty is that we all have to face it eventually, if not by proxy, then certainly on a one-to-one basis. Maybe it is this sense of certainty that comprises part of what drives us to find ways of representing it. We have a need to confront this inevitability because although we might try to hide away from it, life and death are juxtaposed from the start. My interest – apart from being like every other human who will one day know the dark scythe’s remorseless swing – is in looking at it through the lens of art.

Let’s look at something a century or so older than Arcimboldo’s work. This piece, created by Master IAM of Zwolle c. 1480-1490, at first glance this is repellent: grinning skulls, a writhing snake, and rotting, gnarled corpses residing in a dusky crypt might not be something that we would put on our walls at home, but this Allegory of the Transience of Life is replete with meaning and soulfulness.

The Renaissance mind was deeply concerned with the afterlife. This awareness of death and the need to prepare in life for what came after was paramount. This Netherlandish engraving, with its skulls, snakes, and decay speaks a loud reminder of the importance of inner spiritual life, affirmed by the inscriptions which, according to the British Museum, “reinforce the central theme” of living a pious and thoughtful life and to die well. Often printed in large numbers and therefore affordable, these engravings were used for meaningful contemplation of life and death, not to mention feeding and reinforcing deep-set religious and spiritual values.

The idea of mortality never gets old though, so how about taking a look at Beth Lipman’s One and Others?

Made in 2011, this artwork comprises a black box and an array of glass ephemera. The box is a coffin set on trestles as it would be in a funeral parlor or a church. The coffin was created to fit Lipman’s own body, giving it a strong personal dimension. It feels deeply honest – an acknowledgment of her relationship to her own mortality – and gives rise to our own thoughts on the subject.

The glass provides an ethereal visual beauty, reflecting and refracting the light. It shimmers with crystalline life in stark contrast to the black box upon which it sits. In this duality, we find meaning: the light of life versus the darkness of death; the frivolous nature of light as it bounces off complex surfaces against the looming, simple shadow beneath it; the fragile, breakable nature of the glass against the solid wooden casket; the temporary nature of the glass flowers and objects, of life, against the apparent permanence and finality of death.

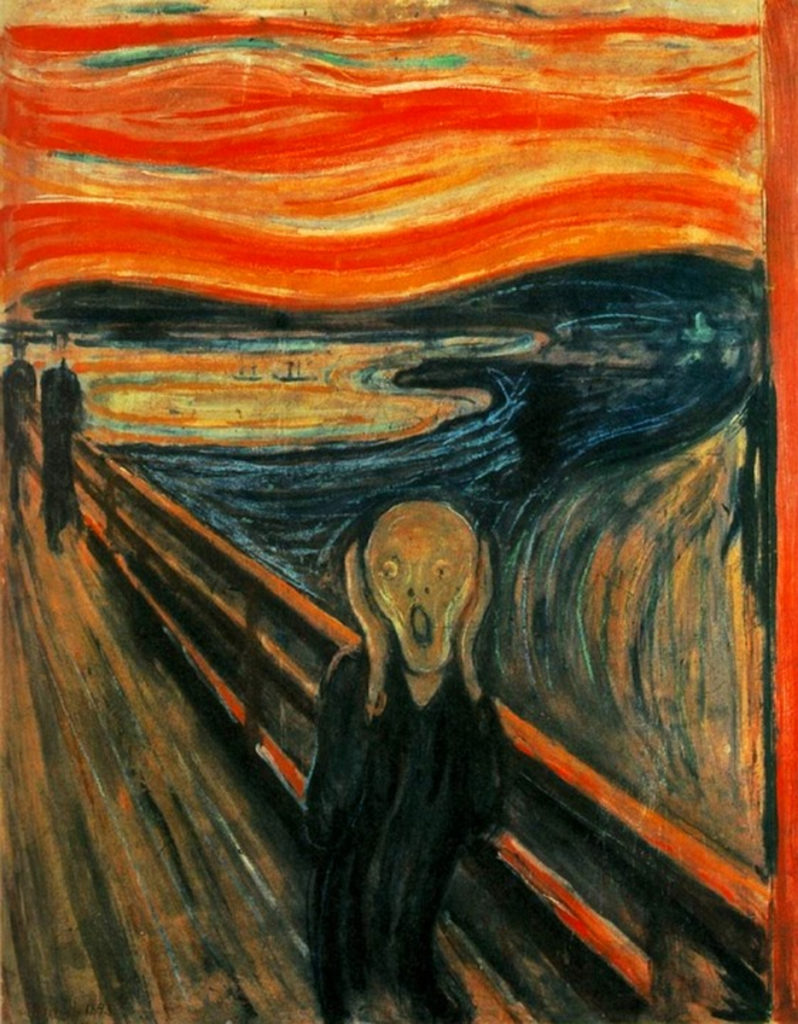

Death can also mean the disappearance of the body and mind. A morbid fear of disappearance seems aptly represented by one of the most famous images of our time: Munch’s The Scream.

Munch wrote in his diary in 1892 that he “sensed an infinite scream passing through nature” as he stood, unwell and exhausted, at the side of the road. The perspective used distances his friends as they recede away seeming not to notice the distress of the figure in the foreground. The man is bent out of shape, becoming one with the agony of the screaming landscape. The image is wracked with his sadness, his fear of being destroyed, and his terror of becoming nothing. The straight fence is all that separates the figure from the landscape, and thus from annihilation.

Although this painting is not specifically about death, it highlights the flimsy nature of the life that we have. We are separated from death by almost nothing at all: a veil of luck and small acts of taking responsibility for our own well-being. This painting, from that point of view, shows the desolation that absorbs us if we spend too much time thinking about it.

Where do we go next? Master IAM seems certain that there is an afterlife, otherwise, why bother to warn us of life’s fleeting nature? Why instruct us to prepare for the ultimate journey? Lipman’s artwork on the other hand seems to suggest finality, a void of black nothingness once the glass has shattered. Munch seems to be something of a nihilist! How can we reconcile these views with our sense of the meaning of life? Sometimes it’s a “glass half empty, glass half full” situation, but how do we know how full or empty our glasses really are? So many questions.

At this point, I turn to artists who use levity to express the impossible conundrum of being human. An element of black comedy in art can make sense of things when all other methods have descended into the absurd. Here are my favorite pieces by James Ensor which help me to navigate the convoluted relationship that we have with death.

Why would skeletons be fighting over a pickled herring? They are ridiculous, and their wisps of hair, clothes and comically distorted features add to their silliness. As I wrote in a previous article about Ensor he has a tendency, like Munch, to look inwards. But, instead of ‘vast vacuums of bleak desperation, he paints a more colorful and lively impression of his internal landscape. He points out the comedic absurdity of life while simultaneously implying its impermanence. We may fight over herrings, but we are all dust eventually – dark humor indeed!

Ensor painted this in response to negative appraisals of his work by the art critics of his day. His work is the herring and the skeletons are the critics! A different interpretation might be that life is the herring, and the skeletons are… you decide.

In Masks Confronting Death (1888) the Death figure is central while masked onlookers gather around, close enough to touch. It seems to me that the humor lies in the fact that as masked individuals the figures surrounding death might feel protected by their anonymity, as though their masks act as a shield, but of course, this is not so. They gather as though drawn by some irresistible calling, a curiosity to know more. There is perhaps an unconscious recognition of the destiny of all things, but it has been dressed up as a masquerade that is as inconsequential as death is inevitable.

We have a need to confront our own impermanence and we do it in many different ways. Ensor is one of my favorites because his work is questioning and investigative. Despite his dark themes, Ensor retains a sense of positivity (and dry humor) while rubbing up against a difficult subject. Death is ultimately a mystery, at least on this side of the veil. Thinking about death is natural, and to some extent healthy, but if we become too absorbed by it, only madness awaits!

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!