The Greatest Male Nudes in Art History (NSFW!)

Nudity started being an important subject in art in ancient Greece. The male body was celebrated at sports competitions or religious festivals, it...

Anuradha Sroha 8 October 2024

We’re here to let you in on a pretty widely known secret about art history: it is all about sex. Nude representations of men and women caused scandals throughout the centuries (female nudes of course more often, unfortunately). Often dressed up in a religious or mythological costume they often violated “the good taste” of the epoch because of their straightforwardness.

In celebration of the wildly erotic tendencies of artists over the centuries, we’ve put together a list of the most jaw-dropping female nude painting.

Although the Greeks had no problem showing their male Gods and figures without clothes, the same rules did not apply to women. Even Aphrodite, the Greek Goddess of love, was always sculpted wearing loosely-draped robes. But in the mid-fourth century BCE, a sculptor named Praxiteles gave form to a naked Aphrodite. His Aphrodite, undressing for her bath and completely naked, her right hand modestly covering her pubic area, was the first life-size representation of a nude female form.

Originally commissioned as a cult statue for a temple in Kos, Praxiteles made two versions: one clothed and one nude. The temple bought the clothed version, but private citizens of the town of Knidos bought the nude version and put it on public display in an open-air temple. The naked Aphrodite soon became a sensation: people came to visit it from all over Greece, numerous copies were made, and the statue was written about throughout the Mediterranean. Praxiteles’ statue has not survived. But because it was one of the most copied statues in the world, Roman replicas and descriptions that survive today give us a pretty good example of what the original looked like. This Roman Venus is a smaller-scale copy of Praxiteles’ original.

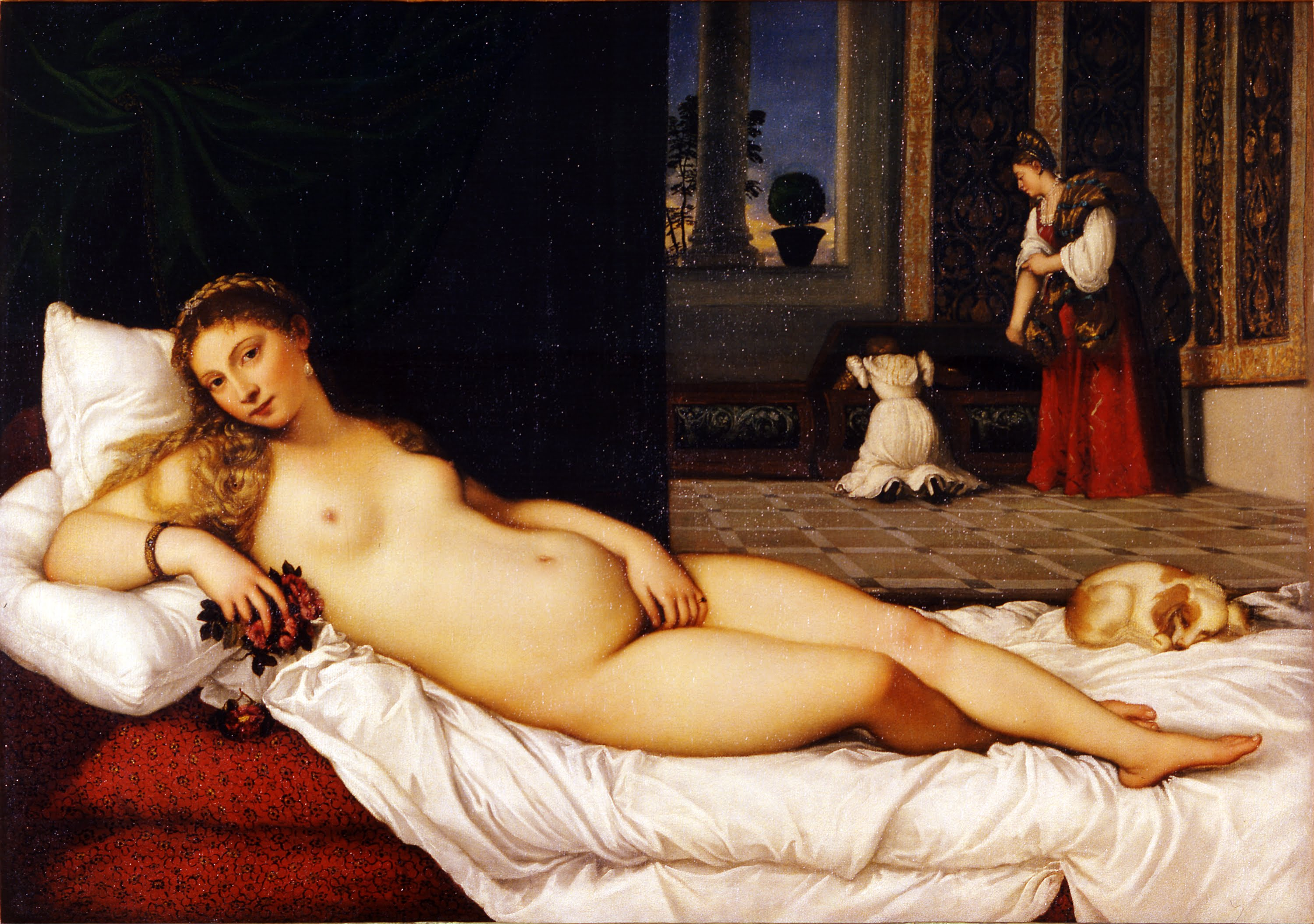

Mark Twain once called Titian’s Venus “the foulest, the vilest, the most obscene picture the world possesses.” Just look at Venus’ hand, it looks very suspicious. It is probably a portrait of a courtesan, perhaps Zaffetta. Even the indefatigable finder of allegories drawing on Renaissance Neoplatonism, the art historian Edgar Wind, had to admit that in this case “an undisguised hedonism had, at last, dispelled the Platonic metaphors.” With her unabashed nudity and strong gaze into the viewers’ eyes, the nude female in this 1538 work of art is undeniably erotic.

This painting is the only surviving nude by Diego Velázquez, a Spanish artist of the 17th century. Such paintings were really rare during those times and due to their nude content, it was officially discouraged by the Spanish Inquisition. But Velázquez, being King Philip IV’s painter, did not fear making such paintings. But there is another story connected to this painting – on March 10, 1914, this painting was damaged by a woman named Mary Richardson.

At first, it was stated that the reason for this action was provoked by the arrest of a fellow companion, but later in 1952, when interviewed she said that she destroyed the picture because she didn’t like the way men visitors gazed at it all day long.

The Nude Maja is part of a two-painting series, where the second work is The Clothed Maja by Francisco Goya. The painting is controversial for the apparent reason of exposing a naked woman – it will go down in history as “the first totally profane life-size female nude in Western art“ — thought to be at least one of the first explicit depictions of female pubic hair. At the time of its creation, the Catholic Church banned the display of artistic nudes, so Goya’s nude woman and its more modest counterpart, The Clothed Maja, were never exhibited publicly during the artist’s lifetime.

What adds to the controversy is that later in 1930, two sets of stamps depicting The Nude Maja were privately produced. It was the first time a stamp represented a naked woman. The Spanish postal authorities had approved them, but the US government banned the stamps from entering the country. The US returned mail bearing the stamp.

The woman has no explicit reason to be naked – she is not a mythological figure but a normal lunch companion – and her partners are both clothed. The nudity wasn’t even the most shocking part of this painting though. Manet’s painting style and his refusal to make subtle gradations between the light and dark part of the painting, as well as his deliberately shallow depth and perspective, were also considered avant-garde.

When Olympia went on show at the Paris Salon in 1865 it caused an outrage. Critics at the time described this oil painting as “vulgar” and “immoral.” All because of the nude subject’s confrontational gaze (looking directly at the viewer) and the artist’s allegedly “blatant” depiction of a prostitute. They also complained the woman’s slender physique made her look like a young girl and that the numerous objects featured in the painting were clear signs that she was indeed a “lady of the night.”

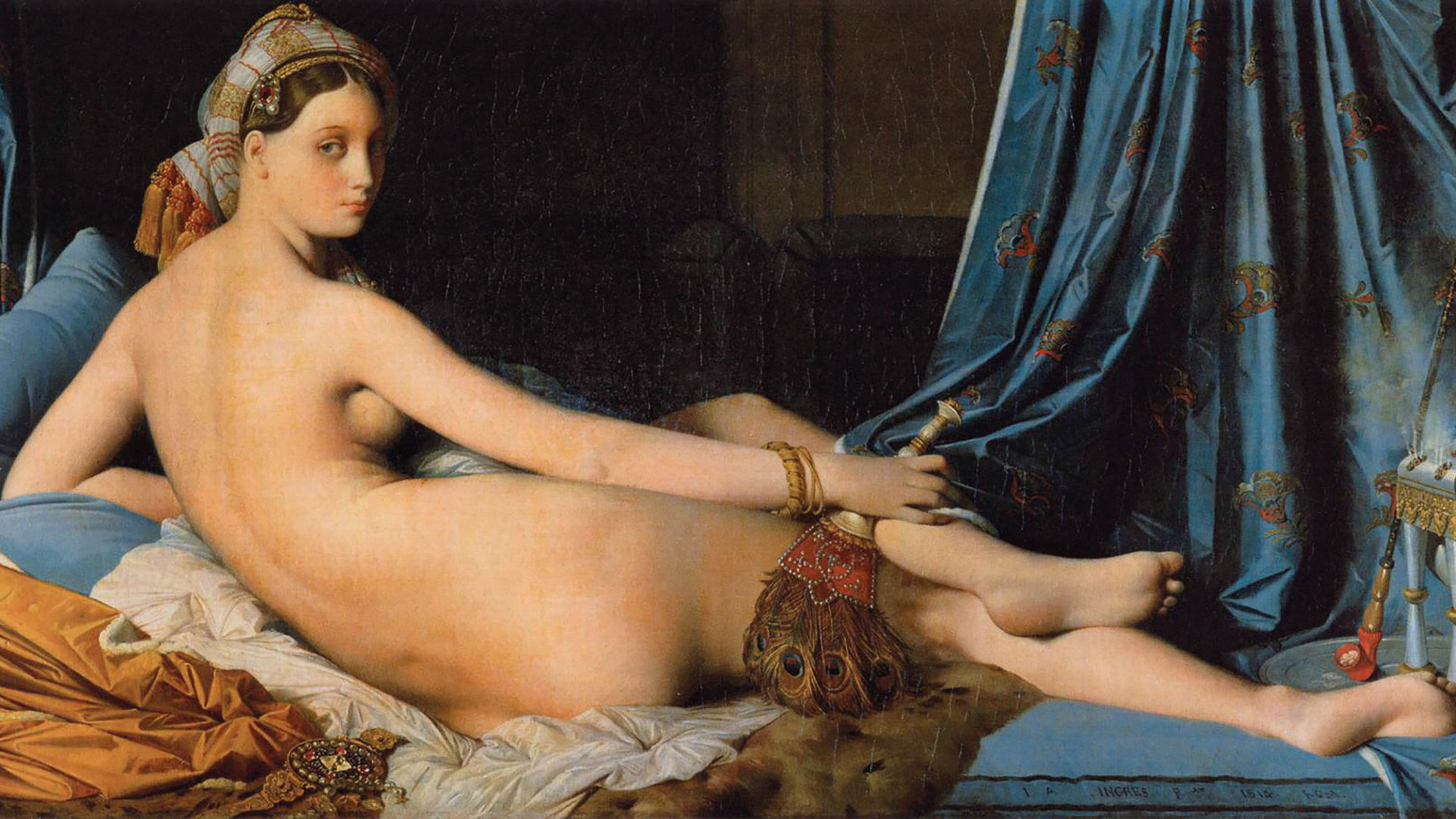

Ingres’ contemporaries considered the work to signify Ingres‘ break from Neoclassicism, indicating a shift toward exotic Romanticism. Grande Odalisque attracted wide criticism when it was first shown. Not because of the nudity of the subject, but because of the elongated proportions and lack of anatomical realism. One critic remarked that the work had “neither bones nor muscle, neither blood, nor life, nor relief, indeed nothing that constitutes imitation.”

Stemming from the initial criticism the painting received, the figure in Grande Odalisque is thought to be drawn with “two or three vertebrae too many.” Critics at the time believed the elongations to be errors on the part of Ingres, but recent studies show the elongations to have been deliberate distortions.

This realistic, graphical eroticism in the name of painting still has the power to shock and trigger censorship. For example, it gets banned on Facebook whenever we publish the article Few Comments On Courbet’s Origin of the World. Courbet tried to violate the public and he loved doing that via his paintings. He made The Origin of the World in protest against the Academy, where students were trained to draw statues with stereotyped and camouflaged bodies. Courbet hated this formula and said he could only paint what he saw.

This print is a perfect example of Japanese Shunga art. It depicts a fisherman’s wife deriving pleasure from a rather unique encounter with an octopus. But do you recognize the artist’s name? Yes, the man behind The Great Wave off Kanagawa had more than landscape likenesses up his sleeve.

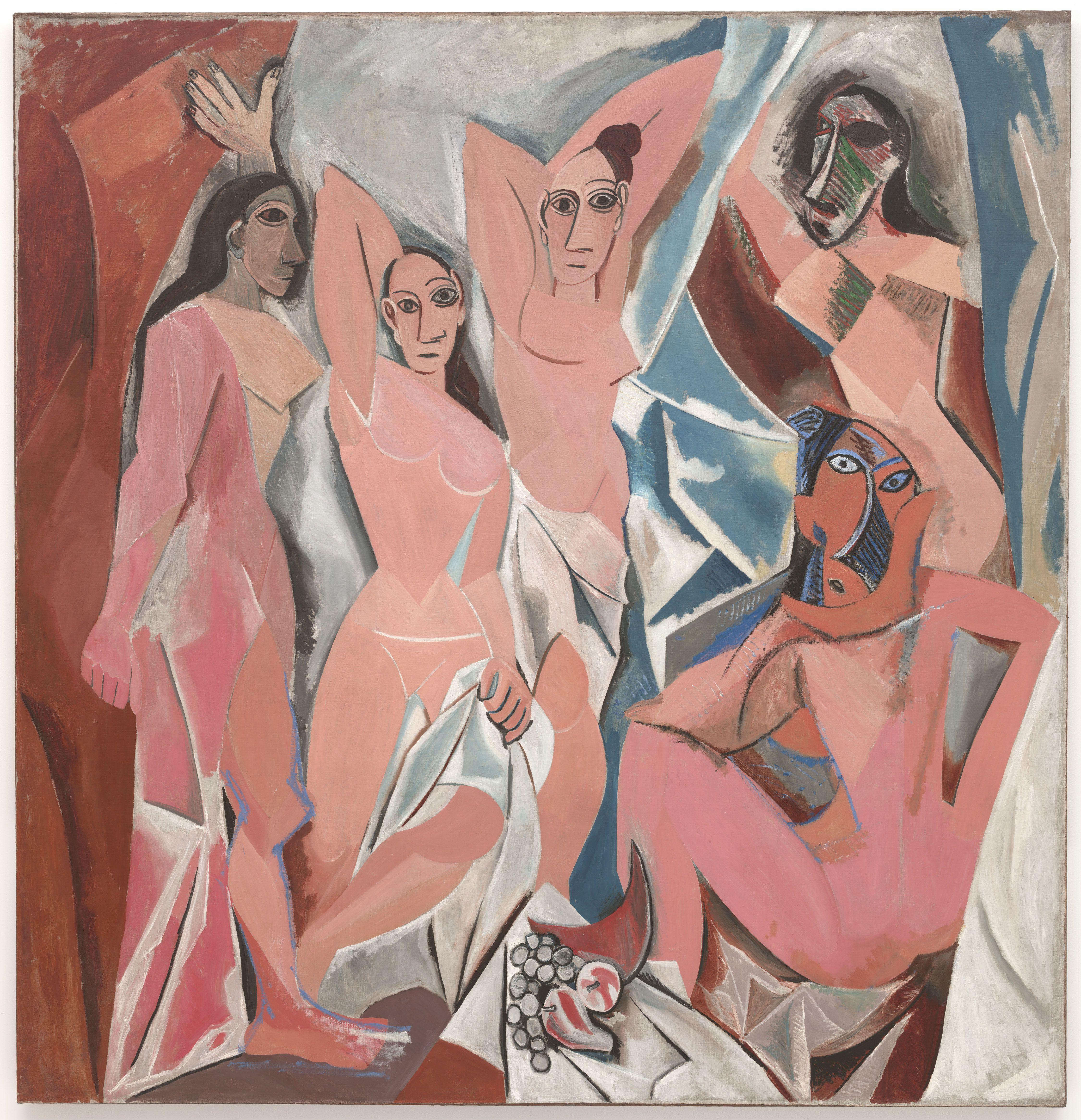

This Picasso painting provoked widespread outrage when it was originally exhibited in 1916, with critics and members of the public describing it as “immoral.” Not only had Picasso painted five prostitutes, but his revolutionary style of depicting them using geometric shapes and bold colors was simply too much for critics and the public at the time, who initially described this now-famous painting as “grotesque.”

According to reports at the time, Picasso’s main art rival, Henri Matisse, was furious after seeing the painting and claimed his own work had been overshadowed and devalued by Picasso’s “hideous whores!”

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!