A New Take on the Iconic Girl Reading a Letter by Vermeer

The recently restored Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window by Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) is often said to be that of a young woman reading a...

Tom Anderson 26 September 2024

For centuries, Black women appeared in Western art as slaves, servants, or exotic novelties. But as regal queens and leaders? Shamefully not. We will delve into the unknown histories of Black queens in Europe and also take a closer look at contemporary artists’ approach to subjects of blackness and official portraiture.

Let us remember the woman bearing flowers in the background of Manet’s famous nude Olympia of 1863. This is typical of the trend for Black women as background interest, rather than foreground importance. But thanks to recent discoveries we now know her name, Laure, a Black maid whom Manet knew and painted a few more times. The Kitchen Maid by Diego Velazquez from around 1620 is the main focus of the piece, but the title tells us this is no woman of power.

In the modern world, this systemic racism is unacceptable. Amy Sherald painted First Lady Michelle Obama in 2018; a tender yet incredibly regal image. And to bring us directly to the present day, Meghan Markle joined the British Royal family just a few years ago. But, Markle, whose mother is Black and whose father is white, is actually not the first Black woman to join the British royal family.

Let’s examine the case of Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz who was born in 1744. Many Englanders were in denial at the time, but it seems that the wife of King George III, who was Queen from 1761 until her death in 1818, was directly descended from Margarita de Castro y Sousa, part of a Black branch of the Portuguese Royal House.

Historians often describe Charlotte as the first Black Queen of England, but in fact, we have one even earlier example. Philippa of Hainault (1315-1369) was the wife of Edward III. She was the daughter of the Count of Hainault the ruler of a historical region in the Low Countries, an area once ruled by Moorish tribes. She was described by contemporaries as being “brown of skin.”

We may never know for certain, from looking at portraits. Royal artists of both periods were expected to play down, soften or even obliterate “undesirable” features in a subject, male or female. But art historians do seem to agree that there are African characteristics in that lovely face.

Back to the modern day, American artist Kerry James Marshall has earned acclaim for placing Black figures center-stage within all his paintings. Marshall has said:

The blackness of my figures is supposed to be unequivocal, absolute, and unmediated, They are a response to the tendency in the culture to privilege lightness. The lighter the skin, the more acceptable you are. The darker the skin, the more marginalized you become. I want to demonstrate that you can produce beauty in the context of a figure that has that kind of velvety blackness.

Kerry James Marshall, in: Many Mansions, interview, Art21.

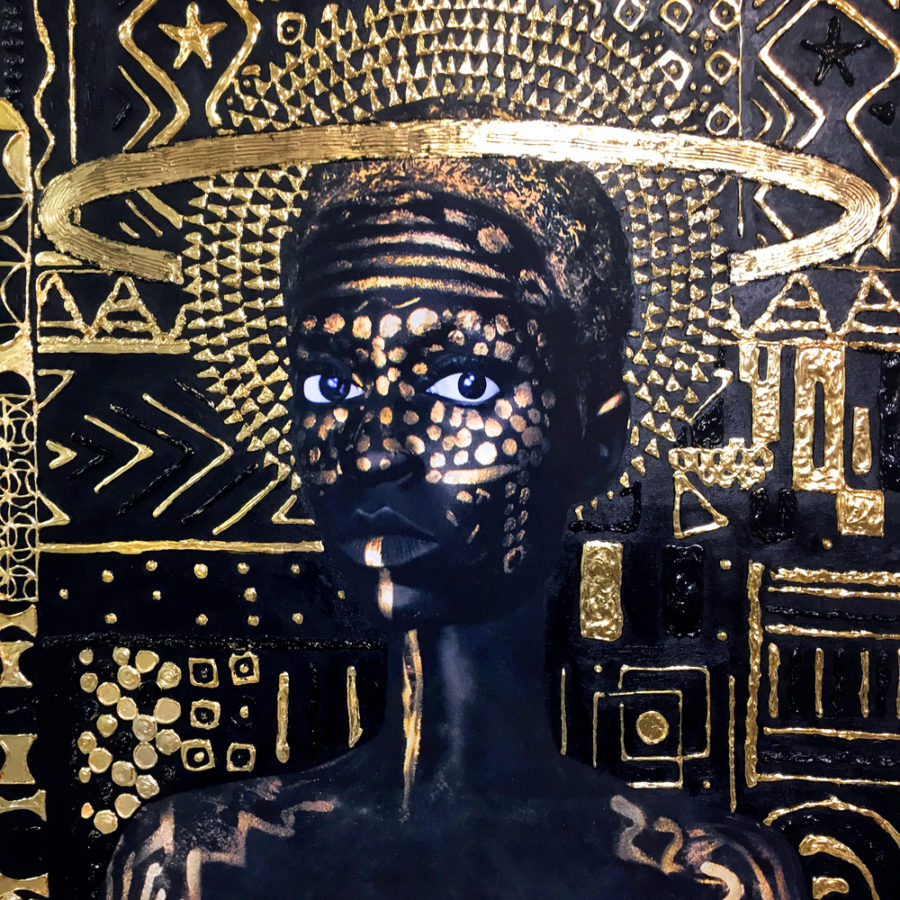

Lina Iris Viktor is a British-Liberian visual artist based in New York. The New York Times described her paintings as “queenly self-portraits with a futuristic edge.” Viktor’s work is based on ancient Egyptian and African symbolism. Each painting is molded in resin and then coated with 24-carat gold leaf and black paint. The use of gold is an affirmation of the wealth and richness of African heritage.

Young Black American artist Jeromyah Jones is also interested in how we represent “regal” lines. In 2012 he presented Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth with a 5 x 4 foot oil painting entitled The Judgment Day at I.H.O.P.

His latest work is a diamond-shaped oil painting on canvas entitled, The Regality of Queen Regai. The painting depicts Gabrielle Tinsley of Petersburg, Virginia, USA. Speaking to me recently, Jones said:

I created this image to exemplify the significance of the world seeing Black women as royalty. In an age where negative stereotypes that do not define Black women are constantly projected on television, I am showing that being clothed with character that transcends social class is what lasts. As society often focuses on women’s physical dimensions, my painting and poem (also inscribed in the painting) focuses on the presence beyond the body.

Jeromyah Jones, in conversation with the author.

Jones, and other modern artists, ask us to re-think how royalty (and therefore power) can be portrayed. Looking over our shoulder into classical paintings of the past, but also looking ahead into the 21st century.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!