Masterpiece Story: Young Bacchus by Mary Beale

Mary Beale is a rarity: a prolific, well-documented, successful, 17th-century woman artist. Her painting of Young Bacchus perfectly illustrates how...

Catriona Miller 10 November 2024

11 September 2023 min Read

Soon after Château de Pierrefonds was displayed, Emperor Napoleon III restored the actual Château de Pierrefonds in the 1850s under the direction of architect Viollet-le-Duc. Perhaps the emperor was inspired to restore this great castle after viewing Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot’s painting? We will never know. Visit the Cincinnati Art Museum to view this painting and see what you think. Ruins of the Château de Pierrefonds is not just a pretty landscape.

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot was a member of the Barbizon School, which flourished from the 1830s to the 1870s in France. The school was named after the small village of Barbizon about 30 miles (48 km) southeast of Paris, where many artists, including Corot, painted. The Barbizon School rejected the classical conventions of Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin and embraced the direct observations of 17th century Dutch landscapes and the works of English contemporary John Constable. In art history, the Barbizon School is interpreted as a transitional bridge between 18th century Classicism and 19th century Impressionism.

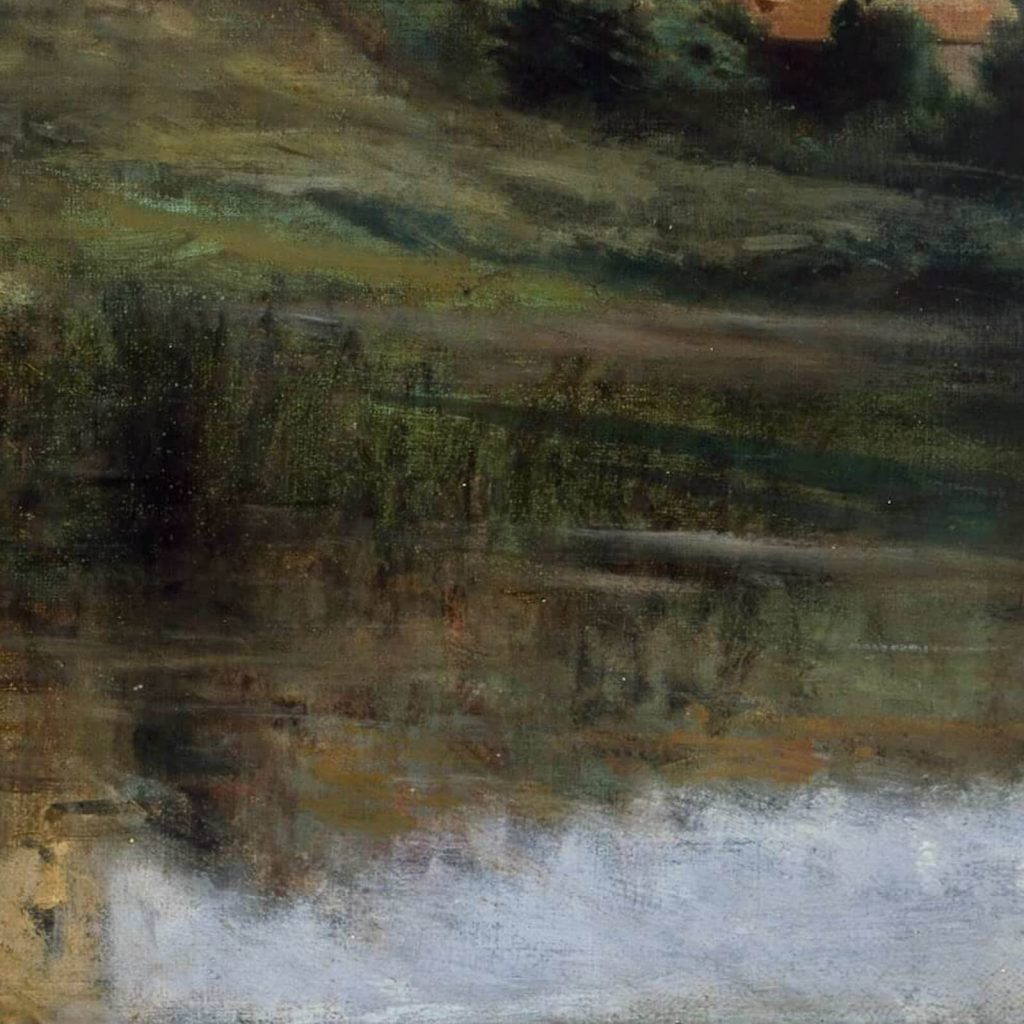

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot painted Ruins of the Château de Pierrefonds circa 1840-45 while in view of the Château de Pierrefonds located 46 miles (74 km) northeast of Paris. Corot believed in painting en plein air (outdoors) so that he could paint from direct observation of nature and rural life. This technique allowed Corot to capture the realistic details of the crumbling ruined castle. Corot captured the famous medieval defensive military architecture of the Château de Pierrefonds through his brilliant use of light and shadow to mould its form against the sky.

The painting is very picturesque with its castle on a hill overlooking the village and water below. By capturing the castle from a low perspective, the castle looms over the landscape and dominates the painting’s composition. Its placement hints to its medieval origins because medieval society was very structured and hierarchical. The medieval lord was at the top of the social order, ruling over his domain. However, the castle is in ruins. Walls are crumbling, and roofs are missing. Like medieval society, it is a former relic. Corot therefore comments on the normal, acceptable, and inevitable cycle of life.

Corot explores the sense of nostalgia in Ruins of the Château de Pierrefonds. During the 19th century there were themes of loss and decay scattered throughout its paintings as people reflected on the lost lifestyles of pre-industrialisation. The Middle Ages, pastoralism, and ruralism became symbols of a missed era. The inclusion of peasants in the foreground hints at this romantic ideology. What are the peasants doing? Are they fishing? Are they picking fruit? One does not know as their hands are blurred. However, one knows that they are most likely peasant women because of the bright blue and yellow fabrics in their hair. What better symbol to explore romantic feelings than a small northern French town with a medieval castle fallen into ruins, surrounded by working peasants and beautiful landscapes?

What is further interesting about Corot’s painting is the visual blending of Beaux-Arts and Impressionist styles. The flowers, clouds, and trees are very impressionistic with their unmixed dabs of color. However, the architecture of the medieval castle and village buildings are so precise and sharp. There is almost a tension of blending feeling and reason. John Constable, who Corot and other Barbizon School artists admired, once said that “painting is but another word for feeling,” and this is so applicable in Corot’s painting. This is not an impartial objective view of some random location. The subject, style, and feelings are all deliberate and intentional.

Ruins of the Château de Pierrefonds captures the spiritual, moral, historical, and philosophical issues of mid-19th century France. Was the medieval era a greater time? If so, did the French fall from this believed greatness? Was the rigid society of pre-industrialization better than the social mobility of post-industrialization? Is the secularization of France and its less Christian observances an improvement or a deterioration? These are all questions provoked by a deeper analysis of this and many other Barbizon School paintings. Ruins of the Château de Pierrefonds is not just a pretty landscape.

“Barbizon School.” Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

“Château de Pierrefonds.” Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

Gardner, Helen, Fred S. Kleiner, and Christin J. Mamiya. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages. 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

“Ruins of the Château de Pierrefonds.” Collection. Cincinnati Art Museum. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

“Ruins of the Château de Pierrefonds.” Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!