Masterpiece Story: Young Bacchus by Mary Beale

Mary Beale is a rarity: a prolific, well-documented, successful, 17th-century woman artist. Her painting of Young Bacchus perfectly illustrates how...

Catriona Miller 10 November 2024

On a small island just out of New York City’s harbor, Lady Liberty greets anyone arriving in the United States from the Atlantic Ocean. Over the years, she has welcomed millions of people, and to this day, millions come to visit her on Liberty Island. But how did she come to be? What is the story behind one of the most iconic statues in the world?

Liberty Enlightening the World, more commonly known as the Statue of Liberty, is a colossal neoclassical sculpture depicting a woman in classical attire. She stands in a contrapposto pose, holding a torch above her head with her right hand. In her left hand, she holds a tablet inscribed “JULY IV MDCCLXXVI” (July 4, 1776, in Roman numerals), the date of the U.S. Declaration of Independence. With her left foot, she steps on a broken chain and shackle. The statue is made of copper plates supported by an interior structure and measures 151 ft. 1 in. (46 meters) from foot to torch.

Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, Liberty Enlightening the World (Statue of Liberty), 1886 (dedication), New York City, NY, USA. Photograph by AskALotl, 2024 via Wikimedia Commons (CC0).

Lady Liberty was a gift from the French people to the United States on the occasion of the centennial of U.S. independence in 1876. The idea for such a monument was conceived in 1865 by French historian and abolitionist Édouard de Laboulaye. Laboulaye wanted to commemorate the perseverance of American democracy and the then-recent liberation of the nation’s slaves.

The sculpture is rich in symbolism. The spikes on the crown represent sun rays extending to the world, and the broken shackle and chain represent the abolition of slavery, which officially ended in the United States in 1865 following the American Civil War.

The sculpture was designed by French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, and the metal framework inside was built by none other than Gustave Eiffel, who would become famous a few years later for the Eiffel Tower. Bartholdi was trying to figure out how to personify the idea of American liberty. Eventually, he settled on a female representation, which was present on American coins of the time and art like the Statue of Freedom atop the United States Capitol building.

Thomas Crawford, Statue of Freedom, 1854–1857, United States Capitol, Washington, DC, USA.

A Franco-American Union was established to fund the project. The French people were to finance the statue, and the Americans would pay for the pedestal. Fundraising efforts were organized in France and across the Atlantic. Among others, a special performance was held in the Paris Opera in 1876, and in the same year, the right arm holding the torch was exhibited at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. During the exhibition, visitors could climb up to the balcony of the torch to view the fairgrounds.

Later, the arm was moved to New York City, where it was displayed for many years in Madison Square Park in Manhattan before being transported back to France for assembly. The head of Lady Liberty was exhibited at the Paris World’s Fair in 1878 to raise funds.

Head of the Statue of Liberty on display at the Paris World’s Fair, 1878. Photograph by Albert Fernique, New York Public Library, New York City, NY, USA.

By 1883, the statue was almost finished when Laboulaye died. He was succeeded in the French committee by Ferdinand de Lesseps, famous as the developer of the Suez Canal. Finally, the following year, the statue was finished and presented to the American ambassador in Paris in a formal ceremony on July 4th, 1884. However, it remained in France for another year, pending the construction of the pedestal, because things weren’t looking as good in the United States.

The funding committees on the other side of the Atlantic were facing great difficulties and had remained inactive for several years due to intense public criticism. The Americans didn’t like the statue’s design or the fact that they would have to pay for the pedestal.

In the U.S., fundraising efforts for the pedestal included theatrical events and art exhibitions; poet Emma Lazarus wrote and placed into auction the now-famous sonnet The New Colossus. The poem was inscribed on a plaque and placed on the pedestal in 1903. Fundraising took a turn for the Americans in 1885 when Joseph Pulitzer placed an ad in his paper, the New York World, inviting readers to donate to the cause. In exchange, Pulitzer printed each donor’s name in the newspaper.

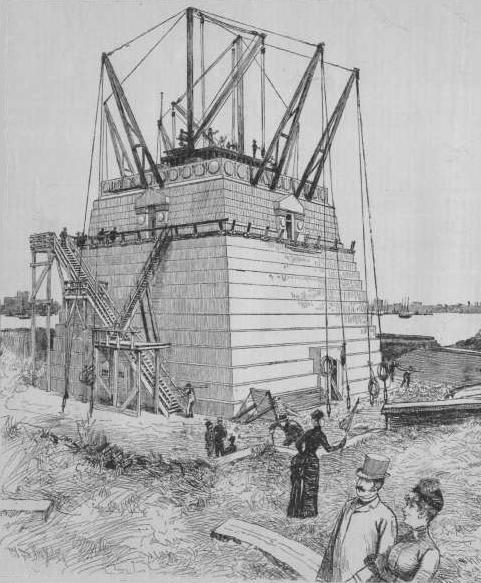

Pedestal under construction in June 1885, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA.

The foundation of the statue was laid inside Fort Wood, a disused army base on Bedloe’s Island, now known as Liberty Island. The Fort is shaped like an 11-point star, and the pedestal was placed on top of it. The Statue of Liberty faces southeast to greet the ships entering New York City harbor from the Atlantic. American architect Richard Morris Hunt was commissioned to design the pedestal in 1881. He proposed a 114 ft. (35 m) pedestal, but due to lack of funding, the committee reduced it to 89 ft. (27 m).

The pedestal’s design incorporates elements from classical and Aztec architecture. Originally, it was to be made of solid granite, but the plans were revised, and it was constructed with concrete. The concrete mass was the largest poured at that time.

Finally, in 1886, everything was ready. The statue was assembled, and the dedication ceremony was held on October 28, 1886.

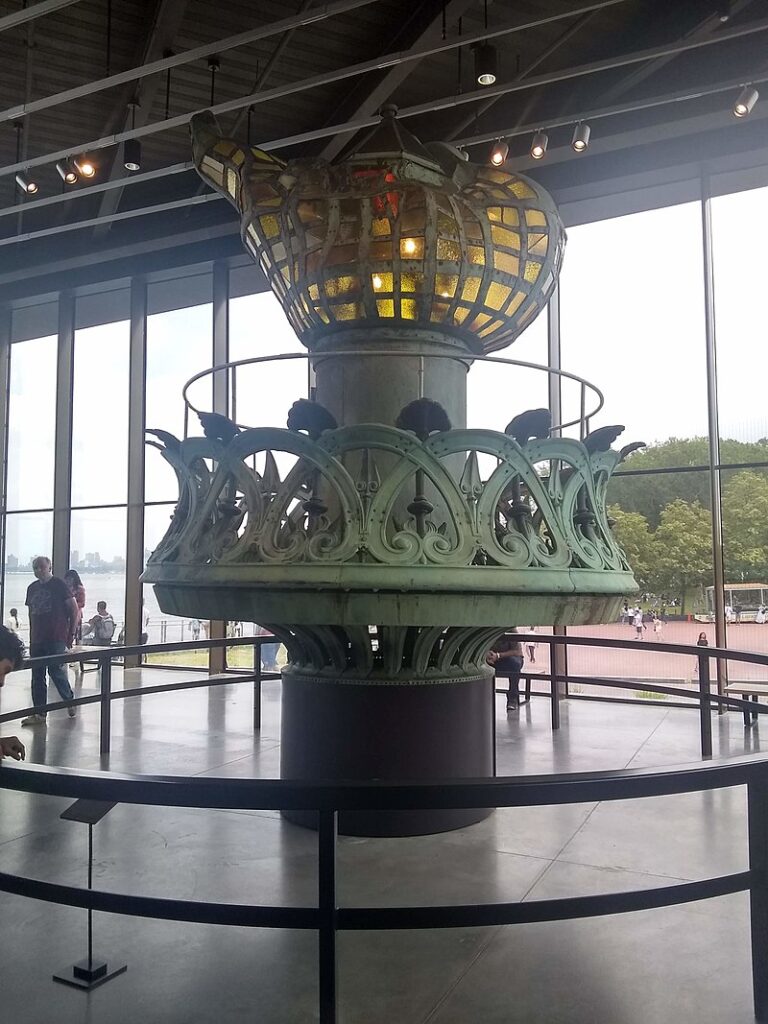

Bartholdi’s original design called for the torch not to be lighted but to be made of copper and gilded to shine in the daylight. However, the torch underwent many modifications in its first 50 years. By 1931, Bartholdi’s design was barely recognizable. The copper was removed and replaced with amber-colored cathedral glass, and numerous holes were cut out on the torch and the surrounding balcony.

The original torch on display at the Statue of Liberty Museum, New York City, NY, USA. Photograph by Epicgenius, 2019 via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

During the 1980s, the statue underwent extensive renovations to mark its centennial celebration. A team of experts determined that the wind and rain had damaged the torch beyond restoration. It was removed on July 4, 1984, and replaced with a replica that followed Bartholdi’s design. The original torch is on display in the Statue of Liberty Museum.

An enduring symbol of liberty, democracy, and freedom, the Statue of Liberty reminds us that all men are created equal. Moreover, the combined efforts of France and the United States are a testament to what nations can do when they put their minds together on a common cause.

View of the Liberty Island, New York City, NY, USA. Photograph by Don Ramey Logan, 2014 via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 4.0).

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!