Nun, Scientist, Artist, Saint: Meet Hildegard von Bingen

Saint Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179), also known as the Sybil of the Rhine, is one of the most renowned figures from the European Middle Ages. She...

Iolanda Munck 18 July 2024

Italian medieval altarpieces rose as fundamental pieces of sacred artistic expression, playing an essential role in both religious devotion and visual narrative. These works, a fusion of painting and sculpture, not only adorned the altars of churches but also served as a medium of teaching and inspiration for the faithful.

Emerging initially as simple panels, Italian medieval altarpieces evolved into more complex, articulated, and folding forms, even made of precious materials. In Italy, the birthplace of the Renaissance and epicenter of European art, altarpieces acquired a distinctive peculiarity. The fusion of the sacred and the profane in Italian altarpieces makes them exceptional examples of the intersection between art, religion, and culture. Art was at the service of the patron’s purpose, enriching artistic expression with a variety of unique influences and styles.

In the 13th century, the appearance of the mendicant orders resulted in a proliferation of religious artistic commissions. The mendicant orders, such as Franciscans and Dominicans, had a clear inclination towards teaching, which led them to seek effective ways of communicating the Christian faith through art. Altarpieces were a powerful means of transmitting religious messages and doctrines to a largely illiterate audience. Their vow of poverty and the absence of goods dissipated any suspicion of corruption, which earned them great popularity in the cities. This popularity translated into the financial backing of the urban bourgeoisie and the nobility, who saw the financing of altarpieces as a way of demonstrating their devotion and obtaining spiritual merits.

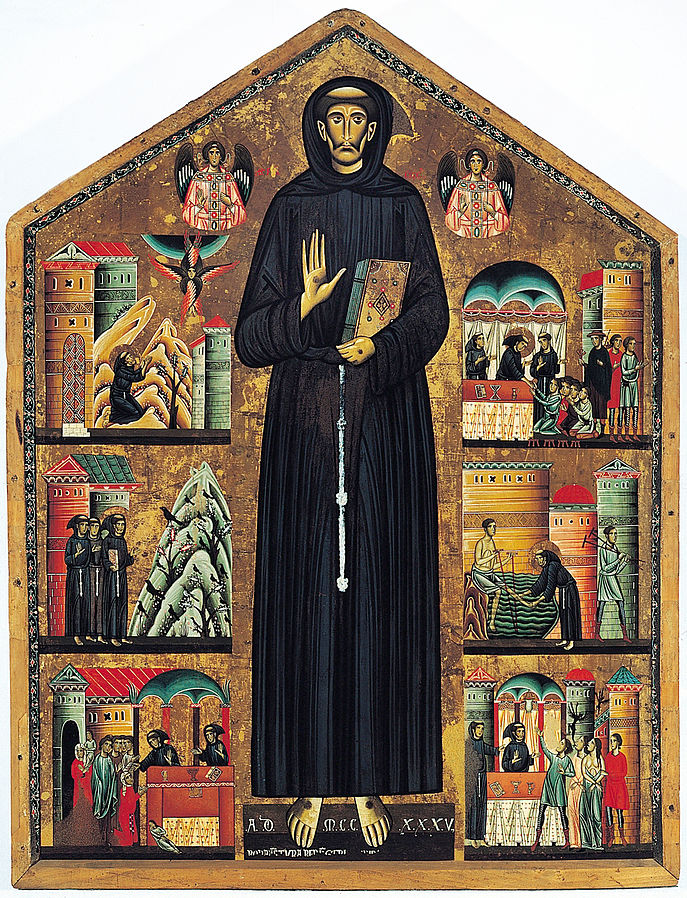

Bonaventura Berlinghieri, Saint Francis of Assisi and Scenes of His Life, 1235, Church of Saint Francis, Pescia, Italy.

St. Francis and the Stories of His Life by Bonaventura Berlinghieri is an outstanding example of how the mendicant orders used art to promote popular devotion. This painting is the earliest known representation of the saint of Assisi, painted just nine years after his death. The work is very interesting in the context of the Italian 13th century because, although the style is still linked to ancient styles, it includes some innovations. It is the first known to treat the theme of the Stories of St. Francis without following a Byzantine model. Moreover, in the representation of the scenes, the author eliminates the horizontal frame typical of the Byzantine panel, distributing them in open squares, which adds a new visual dynamic to the representation.

The Maestà was a recurring theme in medieval and Renaissance altarpieces. Its origin goes back to the medieval tradition of representing the Virgin Mary enthroned with the Child Jesus, influenced by Byzantine art. It became popular from the 12th century in churches dedicated to Mary, reflecting her role as an intercessor between the faithful and God. With the emergence of humanism and religious reform in the late Middle Ages, the Marian cult expanded, making the Maestà a recurring theme among new ecclesiastical and aristocratic patrons.

Duccio di Buoninsegna, Maestá (front view), 1311, Museo dell’Opera Metropolitana del Duomo, Siena, Italy.

An outstanding example is the altarpiece realized by Duccio for the high altar of the cathedral of Siena. This two-sided altarpiece features a central scene with the Madonna and Child surrounded by angels and saints on the obverse, along with 26 scenes from the Passion of Christ on the reverse. Duccio innovated by merging the representation of the Virgin with the arrangement of the saints, creating a unique spatial unity.

The large dimensions of the panel meant that the front part, with the representation of the Virgin, was visible to the faithful from a distance. Meanwhile, the rear, reserved for the clergy, presented the smaller images. In addition, the work stands out for its rich coloring and technical mastery in the detail of the scenes, including depth effects that anticipate the linear perspective of the Renaissance. Thus, the artist achieves a very realistic composition of extraordinary beauty.

Duccio di Buoninsegna, Maestá (back view), 1311, Museo dell’Opera Metropolitana del Duomo, Siena, Italy.

Altarpieces, in addition to their religious and devotional function, became a means of political propaganda for the ruling classes during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Patrons, whether aristocrats, religious leaders, or civil authorities, used them to legitimize their power and reinforce their social status. These commissions not only promoted the image and prestige of the patrons, but also allowed them to display their generosity and devotion, thus gaining the favor and admiration of the community, and consolidating their leadership and authority.

Simone Martini, Saint Louis of Toulouse Crowns Roberto d’Anjou, 1317, National Museum of Capodimonte, Naples, Italy.

The Angevin dynasty exemplifies how aristocratic families used art to strengthen their authority, assert their legitimacy, and demonstrate their power. Louis of Anjou renounced his rights to the throne to join the Franciscans, where he became bishop of Toulouse. After Louis’ death in 1297, his younger brother, Robert of Anjou, began a campaign to canonize Louis, which he achieved in 1317.

Roberto used this fact to link the saints to the Angevin dynasty. To this end, he commissioned Simone Martini to make an altarpiece, known as the Saint Louis Altarpiece of Toulouse. In it, the artist depicted the saint crowning the monarch and references to the house of Anjou can be seen throughout the work, such as the dark blue frame with fleurs-de-lis.

Another type of altarpiece highly demanded during the late Middle Ages in Italy was the ostentatious altarpiece. They emerged as expressions of the opulence and power of the ruling classes. These altarpieces exhibited exuberant ornamentation and rich iconography, with elaborated details such as gilding, precious stone inlays, and intricate reliefs. These masterpieces adorned churches presenting the patrons as pious benefactors and protectors of the faith, highlighting their status and prestige.

Pala d’Oro, 976-1345, St Mark’s Basilica, Venice, Italy.

The Pala d’Oro, located in St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice, exemplifies the splendor and opulence of decorative altarpieces. Commissioned in 976 by Doge Peter Orseolo, it has undergone numerous modifications throughout history to enhance its ostentatiousness. The latest intervention, commissioned by Andrea Dándolo, included the creation of a Gothic frame and the elaboration of wooden panels by Paolo Veneziano to protect it when not on display. This complex work of Byzantine goldsmithing, crafted in gold and silver, has 187 enamel plates, and is adorned with 1,927 gems, from emeralds and pearls to sapphires and rubies.

Baldassarre degli Embriachi, Triptych of the Embriachi (Trittico degli Embriachi), 1400-1409, Certosa di Pavia, Pavia, Italy.

Another remarkable example of ostentatious Italian medieval altarpieces is found in the ivory altarpiece of the Carthusian monastery of Pavia. It was commissioned in the 1390s by Gian Galeazzo Visconti from Baldassarre degli Embriachi. This impressive altarpiece is made of ivory carved from elephant tusks and decorated entirely with gold and ebony inlays. The panels of the altarpiece present scenes from the life of the Virgin, Christ and the Magi. It is interesting to note that years earlier, Gian Galeazzo commissioned an altarpiece with the theme of the Magi for the Basilica of San Eustorgio in Milan. As an anecdote, in 1984, a significant part of the altarpiece was stolen, but fortunately the Carabinieri recovered them.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!